At the moment, I do two things. I'm the trustee and co-founder of a charity called Make Space for Girls, which campaigns for better parks and public spaces for teenage girls and I have just written a book called The Hard Way, which is about following old roads through the English countryside. These would seem to have nothing to do with each other, but in fact they are very deeply connected, both springing from the same basic truth. Which is that society is not very keen on women - or girls - being outside the home.

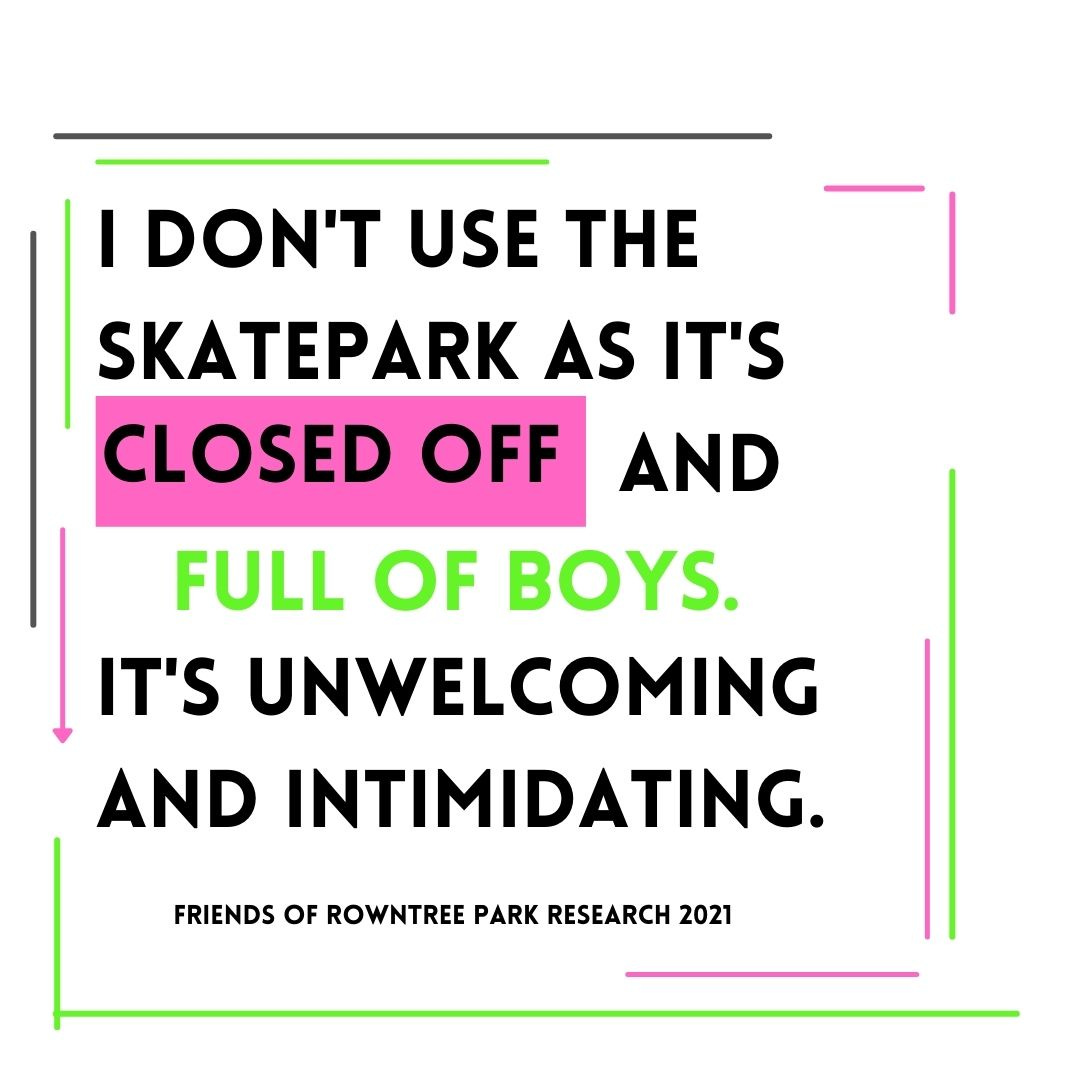

I’m not going to write too much about the work of Make Space for Girls because you can read all about it on the website and Twitter, but the gist of the campaign is that all the facilities provided for teenagers in parks - the pitches, the BMX tracks and the skate parks - end up dominated by teenage boys.

What ought to be community spaces exclude girls from taking part, telling them that they should either be in the shopping centre or at home. And when we talk to girls, they tell us that other places too, like streets lined with betting shops and barbers, also feel coded male and alienating as well.

That’s what I found when I set off walking. The English countryside is in many ways coded male, and sometimes feels to me that as a women it is not where I am meant to be either.

Some of this is for the same reason that girls feel excluded from parks - safety. Or rather the lack of it. For years, it was the fear which stopped me from walking (there’s a whole article to be written about just this, how being made to be afraid is a ball and chain which keeps women close to home), but even when I got over this I would take a detour to avoid white vans parked for too long in lay-bys and track male walkers who were approaching me on the path. And get infuriated by the fact that they don’t have to do the same.

Ahead I’ve seen a man on the slopes but then he disappears. He’s dressed for running and unlikely to be a danger but you never know. By now I should be able to see him again, but he’s not there. Has he hidden down in the ditch? I approach slowly, climbing the steep face of the bank so that I can see him before he notices me. Then it’s fine because a couple are climbing the stile in the next field, heading this way. I’m on alert, processing all these movements like a deer in an open field. When I do see him again, he’s sitting on the grass in the sunshine, cordless headphones in his ear, talking to someone about opportunities in the pharmaceutical industry. He has not had to think for one second about the people around him. I hate him for it.

Other than that, I hear you asking, this is nature, how can it exclude people? The thing is, when you look at it hard, there is very little which is natural about the English countryside. Almost everything you see is man-made. And the word man did not end up in that sentence by accident.

All sorts of unlikely places turn out to be weirdly male when you look at them hard. Take Barbury Castle, which is a hill-fort on the Ridgeway. The word fort suggests that we are in a world of battle and war, even though there is very little evidence that that’s what these great stretches of hilltop banks and ditches were designed for. The view stretches wide over countryside - yes, and Swindon - while the ancient trackway runs off into the distance towards Avebury.

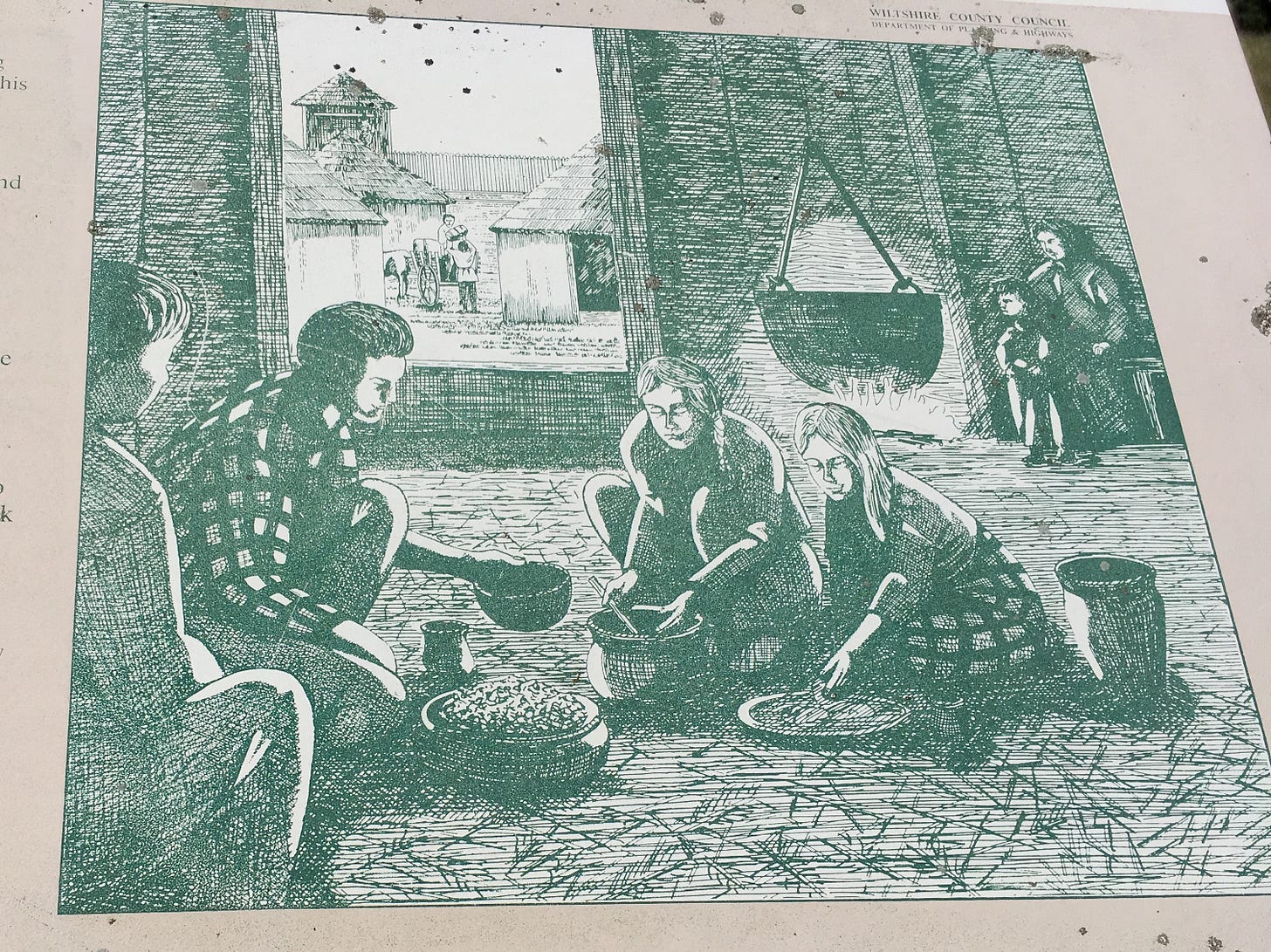

War has been here though - the banks were dug up by American servicemen for a gun emplacement in WW2, while just behind the hillfort still stand the hangars of RAF Wroughton, wartime home of gliders and aircraft and now home to the Science Museum’s collection of big objects like hovercrafts and bombs. The old runway in front is now used by Top Gear for their filming. And if that’s not male enough, the information boards at Barbury have pictures designed to remind me that men do things outdoors which involve leaving the settlement while women stay at home and cook. Even though we have no idea how people arranged their lives in the Iron Age.

Barbury is not an exception. At Liddington hillfort, just a bit further east along the Ridgeway (but still with an excellent view of Swindon), the men have staked their claim with a plaque which commemorates that the hill was beloved of Alfred Williams and Richard Jeffries.

They were both Victorian nature writers, and it’s a reminder that one of the other ways in which the countryside is coded male is because it is men who determine how we see it. Delve into the history of a particular place, as I did with the chalk downland of Wiltshire and Dorset, and you will find that it is men who have set these places down in paint and words.

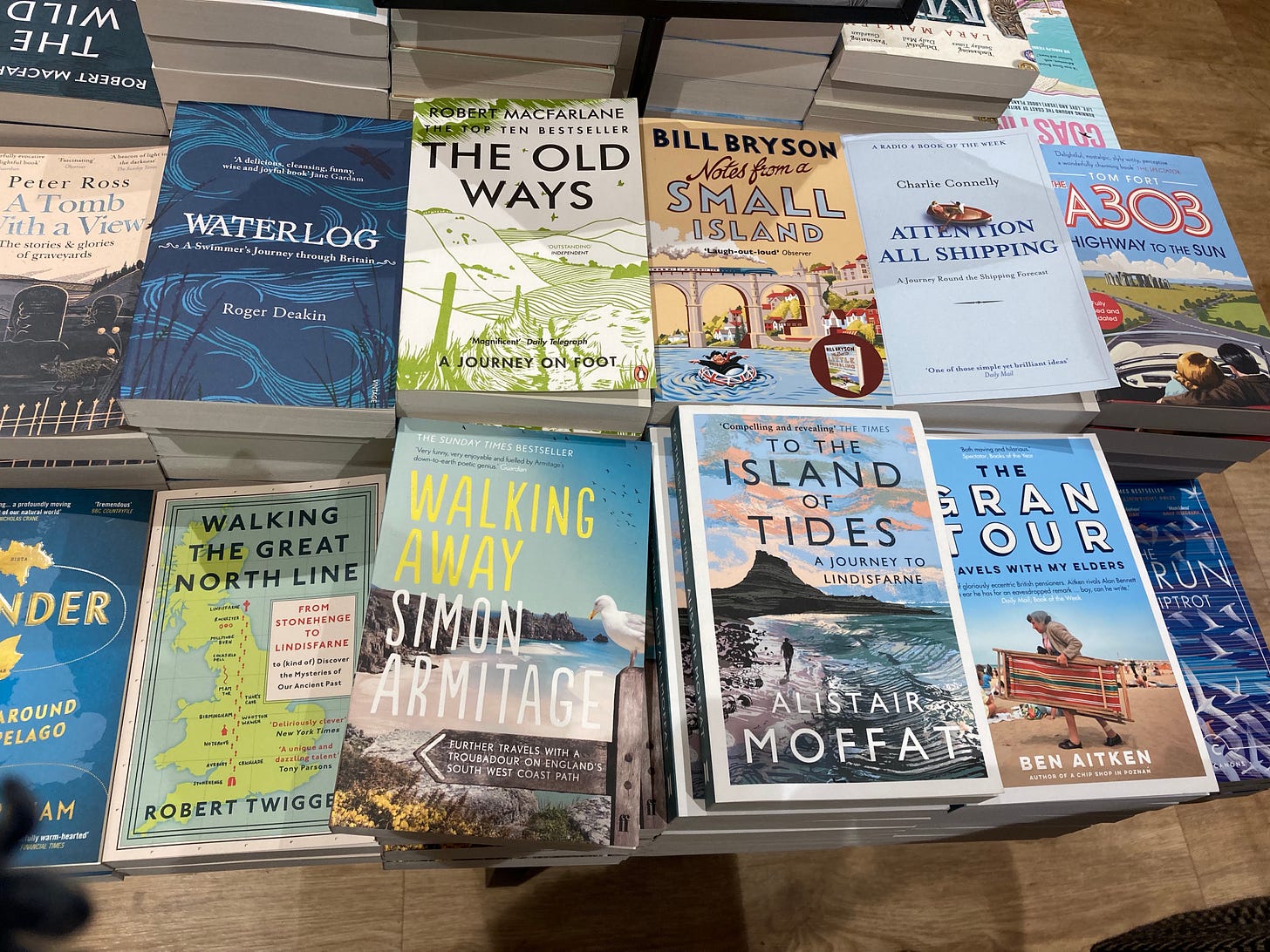

And this persists. Go into your local bookshop and see what it set out on the table of nature writing. Odds are that the vast majority of what’s on offer will have been written by men*.

The good news is that when I delved deeper, I did find some women who had walked and written. But we need to celebrate them more, and that’s one part of what The Hard Way sets out to explore. I’ll write about some of them another day.

*when I proposed this book, the reaction of several publishers and agents was that, oh, that’s been done. By which they meant that two books about women walking had been published recently, one about walking abroad, the other about the history of some women who had climbed mountains. Judging by the bookshop tables, there is no similar limit to the number of men who are allowed to go for a walk and then write a book about it.

If you want to find out more, please do pledge on Unbound to support the Hard Way - you will get a special advance copy with your name in the book and it will get into bookshops sooner.

But this week it would also be great if you could help Make Space for Girls. Over the May Bank Holiday weekend, we’re asking people to go into their local park and count who’s using the teenage facilities. The data will really help the campaign. All the details are on the website.

After reading this, I’m even more pleased that I decided to support The Hard Way. You Echo so much of what I’ve thought over the years.