Here we are once again, standing outside Erlestoke Park and looking at the bleak signs and the fierce fencing.

We know how to have fun. Today, however, we’re going to be looking more at the afterlife of Erlestoke Park and what that tells us about stately homes more generally. With a side order of sociology, but don’t worry, I’ll keep it light.

Ever since 1939, Erlestoke Park has been an institution: first the Senior Officers School and then a prison. In this, it is not alone. Countless country houses and stately homes have become asylums, boarding schools, religious foundations, training colleges and also prisons. Although the main house at Erlestoke has now been mostly knocked down, in other places, such as Tortworth Park and Hewell Grange, prisoners were held in the original mansions.

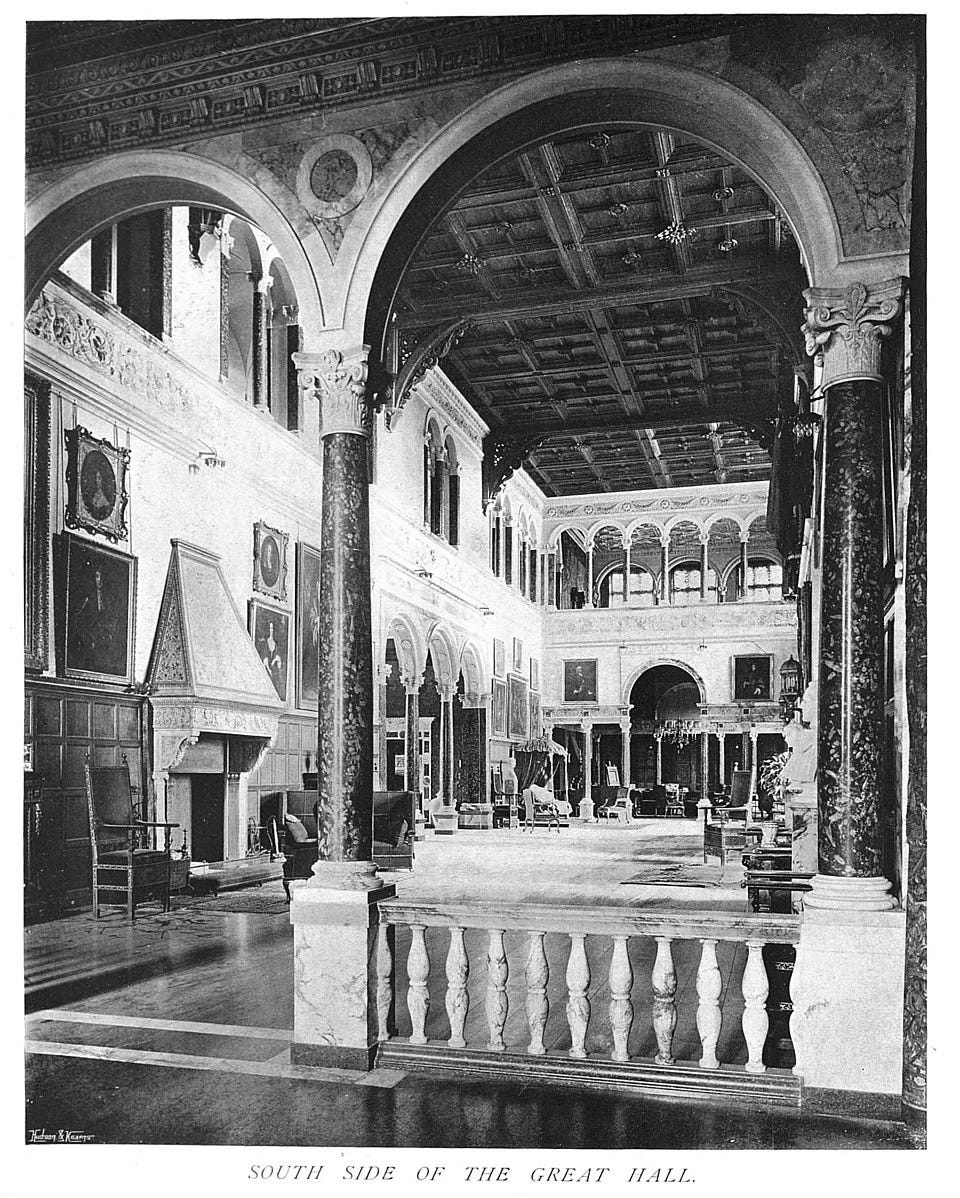

This is a bit of a digression but Hewell Grange is an immense Victorian house and was Grade I listed even while it was still being used as a prison. Which is quite odd. Particularly when you look at images of the interior.

On the face of it, these changes of use are not particularly surprising. These are big places with lots of bedrooms, of course they make good boarding schools and colleges, even asylums.

But stately homes have even more in common with these other institutions than this. That’s the conclusion of a mid-twentieth century anthropologist called Erving Goffman. His book Asylums sets out to define what he calls ‘total institutions’, places where:

…a large number of like-situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life.

The inhabitants don’t have to be felons; in his list Goffman also includes boarding schools, ships, monasteries and old people’s homes. And there is one further example, what he refers to as mansions, aka the Stately Homes of England. So is this true and does it help explain some of what goes on in these places?

Goffman’s tick list for a total institution goes something like this.

they are set apart from ordinary life;

everything takes place under one roof and authority;

activities are tightly structured and sequenced;

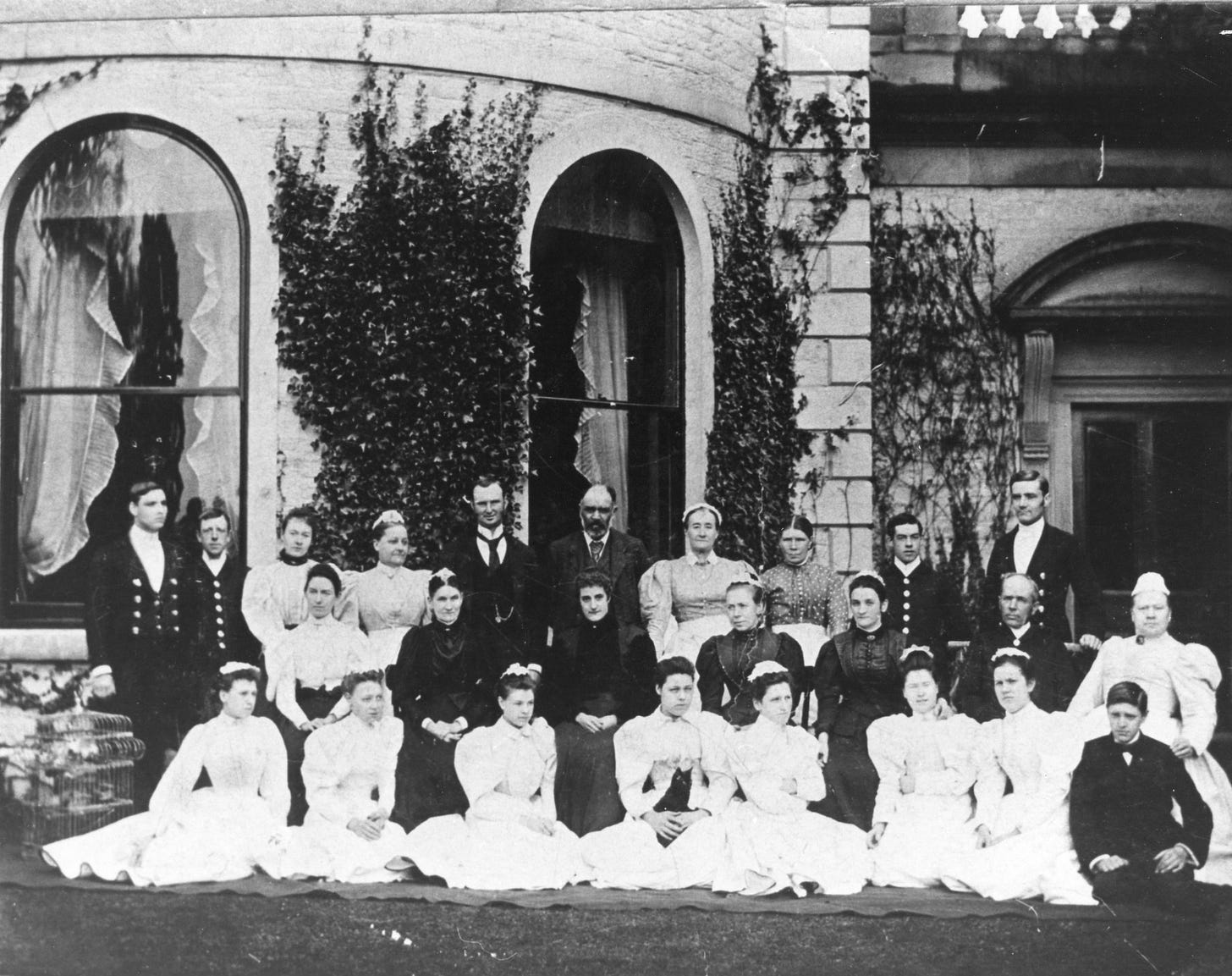

there are batches of people treated alike.

Here is one batch at Brayton Hall in about 1890, who are of course the indoor servants in their uniforms and livery. And this is why thinking about stately homes as total institutions becomes interesting, because it helps us to understand how servants were treated, and why.

Admission to a total institution involves a process of depersonalisation which, Goffman argues, is important in creating these ‘batches’ of people and ensuring that they behave themself. This is exactly what happens in country house service. To start with, once an inmate is approved for admission, they have their old outside identity stripped from them. So servants swap their normal clothes for a uniform in order that they are defined by their role. H.G. Wells’ mother was the housekeeper at Uppark at the end of the nineteenth century, and he saw that every time she returned, she “reabsorbed the hierarchies of below stairs and became institutionalised. For her, the house was a kind of prison she must make the best of.”

This loss of self might even go as far as a changed name. Footmen in particular were often allocated standard Christian names which went with their position, so the first footman would always be William and the second James, regardless of what they were actually called. And so if one of them leaves they will be replaced by another so that the Duke and his family barely notice.

Once admitted, there are many more rules that Goffman identifies as being essential in the total institution. For example, deference is not natural but required by the system, a short phrase which explains considerable and otherwise frankly odd swathes of servant life.

At Chatsworth, servants would be fined if they didn’t toast the health of the Duke and Duchess before a drink, even if they were not at a table, while at Croome Court, Lady Coventry always ended daily prayers with “Lord, please make my servants dutiful”. Goffman also notes that formalised postures of deference are often a part of this system, and this is true of country houses too where, in many places, housemaids were instructed to turn and face the wall if they met a family member in the corridor.

The flip side of this is that insolence was strictly penalised. Any transgressions would mean instant dismissal but there were many pitfalls for the unwary. Even in the early decades of the 20th century, Nancy Jackman lost her kitchenmaid’s job at a big house in Norfolk because her drawing had won a prize at the village fete while her mistress’s entry wasn’t even placed.

And this is barely the half of it; the stately home is also a total institution in its regulated and strict timetable, the total authority of its owner, the way the house is set apart from ordinary life by walls and huge parkland. But I won’t go on.

What is worth saying is that servants themselves understood very well how much they were confined by the stately home, and how closely it resembled one other kind of institution in particular. A cook – and apparently a good one – interviewed for a report in 1916 said, “I should only be too pleased to say goodbye to domestic service. We can only describe it as a prison without committing a crime.” She wasn’t alone in this. When Hilda Newman arrived for her first job as a maid, she saw the pillared and elegant facade of Croome Court but rather than being grateful or astonished to be living in somewhere so beautiful, “I felt as if I had gone to prison… with no hope of anyone coming to rescue me.”

Little did she know that in the case of a few houses, like Erlestoke Park, her vision of the place would one day become the actual truth.