As well as writing about walking and women and spaces which are coded male, some posts on here are going to be devoted to my new hobby of shouting at stately homes. This next one, however, falls into an interesting and unexpected overlap between the two. Because I had never thought of the world of carved, gilded furniture as being a particularly manly place, but that’s what it turned out to be.

For reasons which may or may not be explained at some later date, I was haunting the corridors of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, specifically those dedicated to eighteenth century furniture. I know this place well, as I spent my two years studying in the V&A, based in a room tucked behind these very galleries. But I’d never before registered it as a male space. Only now I couldn't see how I had missed this.

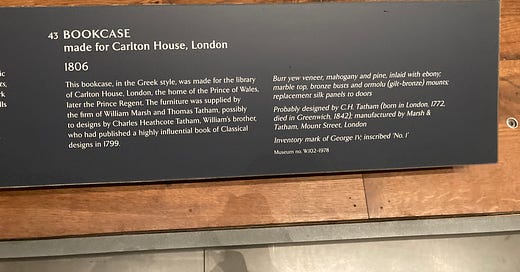

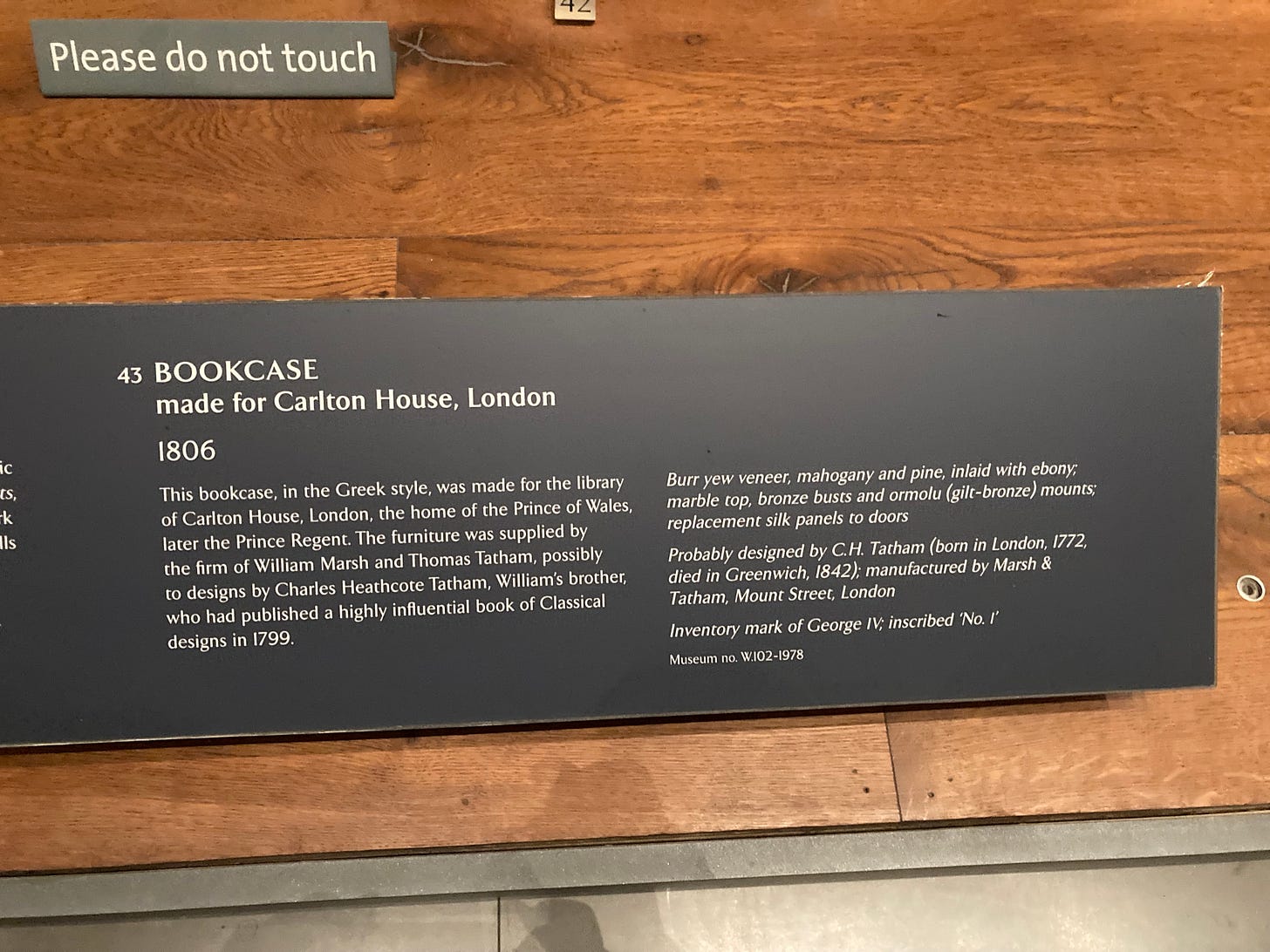

Almost every label followed the same pattern. This piece of gilded and carved and veneered wood was made by a man, for another aristocratic man, possibly emulating the designs of a different man.

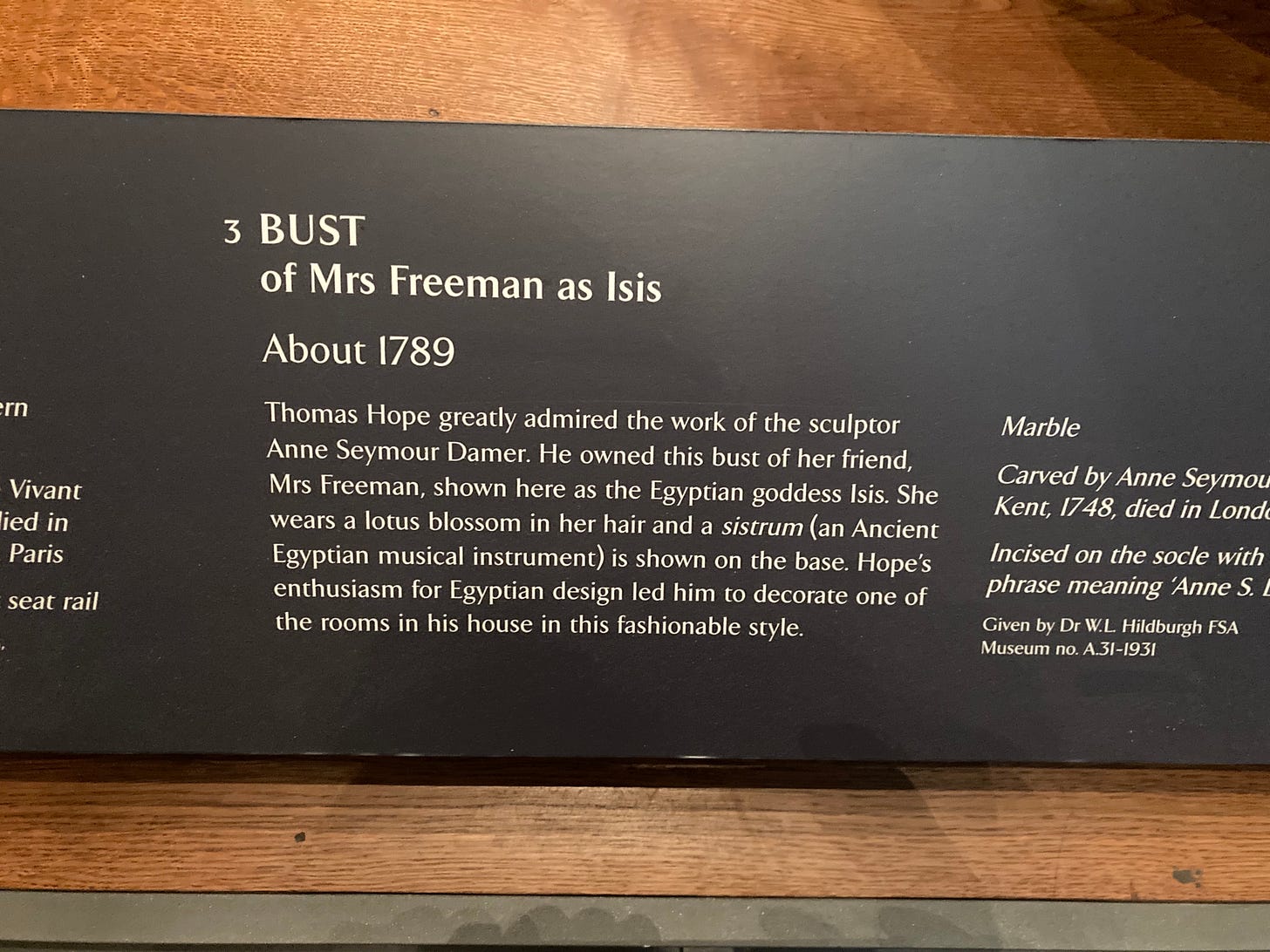

These went on and on and on and the names piled up. What a hall of men this was. Until - hurrah - I found a piece of sculpture which had been created by a woman. Except what had the curators done?

Written a label which had made it all about a man. Excuse me while I hit my head against the desk a few times.

If you were looking for proof that everyone involved hadn’t noticed that their entire gallery was all about men, this was it.

The bust itself was missing from the gallery, but this is what it looks like.

With no thanks to the museum, I can tell you that Anne Seymour Damer sounds like a fascinating woman. She survived an arranged marriage at seventeen to a man who was bad at business but loved expensive suits. They separated after nine years but when he died a year later, the terms of her settlement meant that his family had to pay her an income for the rest of her life. She was twenty eight. Anne taught herself sculpture (how does one even do that?) and lived her best life travelling to Europe, being friends with Robert Walpole and Josephine Bonaparte, writing novels and quite probably being a lesbian. And of course being a sculptor. But why put any of that on a label when you can write about a man instead?

I thought about those labels for the rest of the day. On the train back home, I took a look at the Wikipedia entry for the museum itself, and what a list of men it is too. Here’s the entry for the place I was in, and the only woman is Eleanor Coade who perfected Coade Stone, a kind of artificial stone which ran wild over early Victorian architecture.

Astoundingly few women appear in the whole thing, and most of them are royalty, aristocrats or donors, or some combination of the above. A couple of women architects make it in (Eva Jiřičná and Zaha Hadid), one or two photographers and a few more modern craftspeople. Not one woman artist is mentioned.

There are a couple of fashion designers too, but women have a better chance of being mentioned for wearing dresses than for making them.

…gowns worn by leading socialites such as Patricia Lopez-Willshaw, Gloria Guinness and Lee Radziwill and actresses such as Audrey Hepburn and Ruth Ford.

And then you can have Vivien Leigh, Beatrix Potter and Shirley Bassey. And that, literally, is your lot.

One day when I am really bored I will make a graph of the relative numbers and go and torment the V&A with it.

But there’s actually a more important question, which is what do we do about this? How do we make it better? How can we get women into these spaces? Given that I spent my time in the V&A studying for an MA in Design History, I am better placed than many people to answer this but I don’t have a clue.

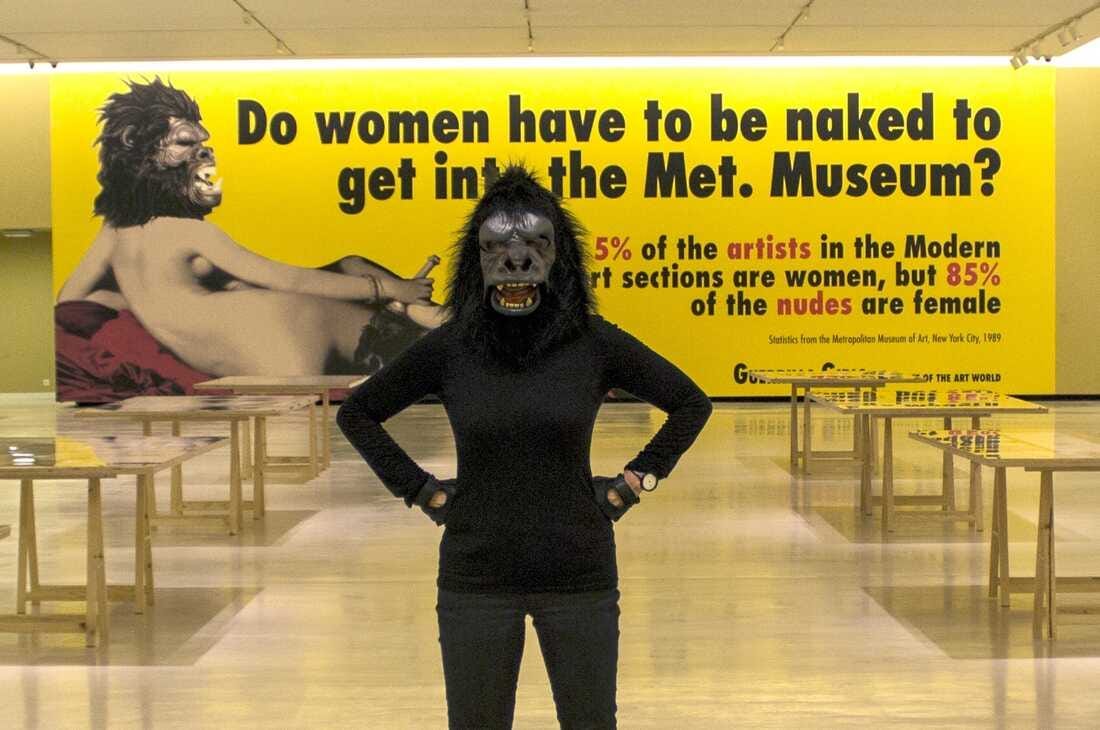

Perhaps the answer is that the first stage is simply to notice that the problem is there. Thanks to the Guerrilla Girls and Art Activist Barbie on Twitter, this is happening in art galleries and museums. So we have a precedent.

Next we can stop writing labels about art made by women which foregrounds the men. That may be enough for now. We can work out what to do after that when we get there.

Meanwhile, if you want to read my book about how the countryside is coded male and how this reverberates through war, art and archaeology, it’s now available on Unbound and you can pledge for an advance copy. And the sooner everyone does this, the sooner it gets into bookshops and we are all happier people because of it.

I’ve noticed this is various museums and galleries, and have been gently teased for grumbling about it.

I think shouting at stately homes is a spectacular hobby, patriarchy or no.