One of the aspects of stately homes that is no longer talked about much now, although it once was, is how many are no longer there. One of the myths of the stately home is that they represent a fixed, immutable England which has always been the same. (I will merely point out here that this is of course something the upper classes would like you to think as this means they’ve always been there too, and so should just remain where they have been, in charge.)

There are so many things I could say about this, so let’s begin in a real place, Erlestoke, in Wiltshire. Earlier this week I found myself outside these gates.

As you might guess, this was once the entrance to a quite grand stately home. But go just a few hundred yards down the road and you will see that all is not as it seems behind the fences. They get bigger, to start with.

Erlstoke Park is now HMP Erlstoke, a combined Category C prison and Young Offenders Institution. Before this, it was run by the army as their Senior Officers School. And in becoming an institution, it is as typical of the stately homes of England as any of the behemoths that we go to visit on a sunny Sunday afternoon. It’s just that this particular story, or perhaps stories, doesn’t get told as often.

The first part of the tale begins in 1939, when Erlestoke Park was requisitioned by the army. Every single large house in England was expected to do its duty - the Air Ministry alone occupied 20,000 properties. The cannier owners tried to acquire safer seeming tenants, like nursery schools or pictures from the National Gallery. The ideal - as happened at Longleat and Castle Howard, was a girls’ boarding school (who usually had to move because their own premises had been taken over by a government department), although in the case of Castle Howard the girls did nonetheless manage to burn down the rotunda.

The worst case was the military. The canny aristocrats would pull strings to avoid soldiers, but in 1939, Erlestoke Park was already in decline after having been sold several times. Being used as a spiritualist retreat and hotel, it was easy pickings, so the house became the Senior Officers School. This remained here until 1961; when the house was badly damaged by fire, they moved into the wings. This was when the site became HMP Erlestoke, the ruins of the house were knocked down and so here we are today, standing on the verge and staring at the razor wire.

But from these bare facts, a number of stories unfurl.

The first is that even though it was a substantial country house (seen above in its pomp in 1825 or so) no one really minded that much when Erlestoke disappeared. Not when it wasn’t returned by the army in 1945, nor when it was burnt in 1950 or finally knocked down after that either. Because in the thirty years or so after the war, the country house was not a universally loved pinnacle of English culture. Only a very few people wanted to conserve them; for most people they were at best an anachronism which could not survive in a modern post-war world. At worst, they were a symbol of class privilege and the exploitation perpetrated by the upper classes.

The country house had been in decline since the 1880s and plenty had been knocked down or used for other purposes over the years - Wycombe Abbey became a boarding school in 1904, while Chiswick House was let as a lunatic asylum as early as 1892. But it was in the years after 1945 that the demolitions, alterations and changes of use reached their peak. In 1955, one house was being demolished every five days. No one wanted stately homes any more. And this is something that we all too often forget.

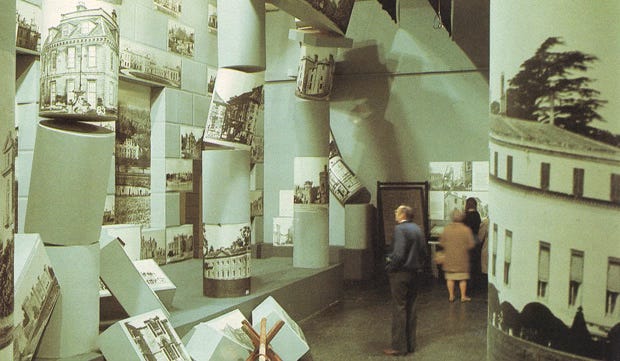

As I’ve said above, I think this act of forgetting is a political choice, but it also has the effect that we don’t remember that they were rescued, never mind how. The change of mind is usually put down to one particular exhibition, The Destruction of the Country House 1875–1975, at the V&A which highlighted the scale of the destruction, but also articulated in public, for the first time, the idea that these places were part of our national heritage.

All of which we now take for granted, and the idea that anyone would want to knock down a stately home, of whatever size, is clearly anathema. But the V&A exhibition was followed ten years later by Treasure Houses of Britain, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, six years in the making. This displayed paintings, sculptures and furniture from 200 different country houses, in spaces designed to look like the rooms of a country house.

For me, this exhibition, which was very much rich people speaking unto other rich people, is the clue as to what was happening. It wasn’t just the case that the country house and its contribution to culture had been rediscovered. Something bigger was shifting underneath the surface.

For the thirty years or so since the Second World War (and possibly for the only time in its entire history), Britain had been a modernist country: a place with square glassy schools, fast roads and motorways, with atomic power (I know) and new factories holding modern industries. There would be equal access to healthcare, light and airy houses and good schools for all.

Until, gradually, the British retreated back into the past. At the same time that the Treasure Houses of Britain exhibition was being designed and organised (it took six years), a television adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead Revisited appeared. This didn’t just have a stately home as one of its starring characters (played in this version by Castle Howard); it was a book about nostalgia and how things were better in the past, specifically in big houses in the past. Suddenly, everyone was looking backwards, and this was the change.

Looking back at the 80s, the shift is clear. All the ruched curtains, squashed from their stately home origins onto smaller domestic windows. And these houses. No longer are we building for the future. My friend Simon grew up on this estate, and even then I could see that the half-moon windows of the front doors had been shrunk down from something much grander and Georgian. Now I also see the pillars and the bay window. On the next street, some of the garages have a portico.

We were all, slowly and unwittingly, being sucked back into an older country. Into the way things were; a world where the future did not belong to us and the upper classes still had the upper hand. And the stately home was the measure of all that we should aspire to be, from our curtains to our porches.

This is why we need to keep remembering that things weren't always the way they are now. Perhaps now it’s time for another rearrangement of the tectonic plates, time for us to see stately homes not just as leisure opportunities, or houses of culture, but in the way that they were understood in the 1950s, as symbols and even tools of exploitation.

Dear Susannah .

Thank you for lifting the scales from my eyes .

Mike

So well written as always. A good read. Must catch up one day Susannah x