Another round of stately home visiting last weekend, trying to get them all in before the visiting season closes. This time it was Norfolk,and one of the houses in our sights was Houghton Hall.

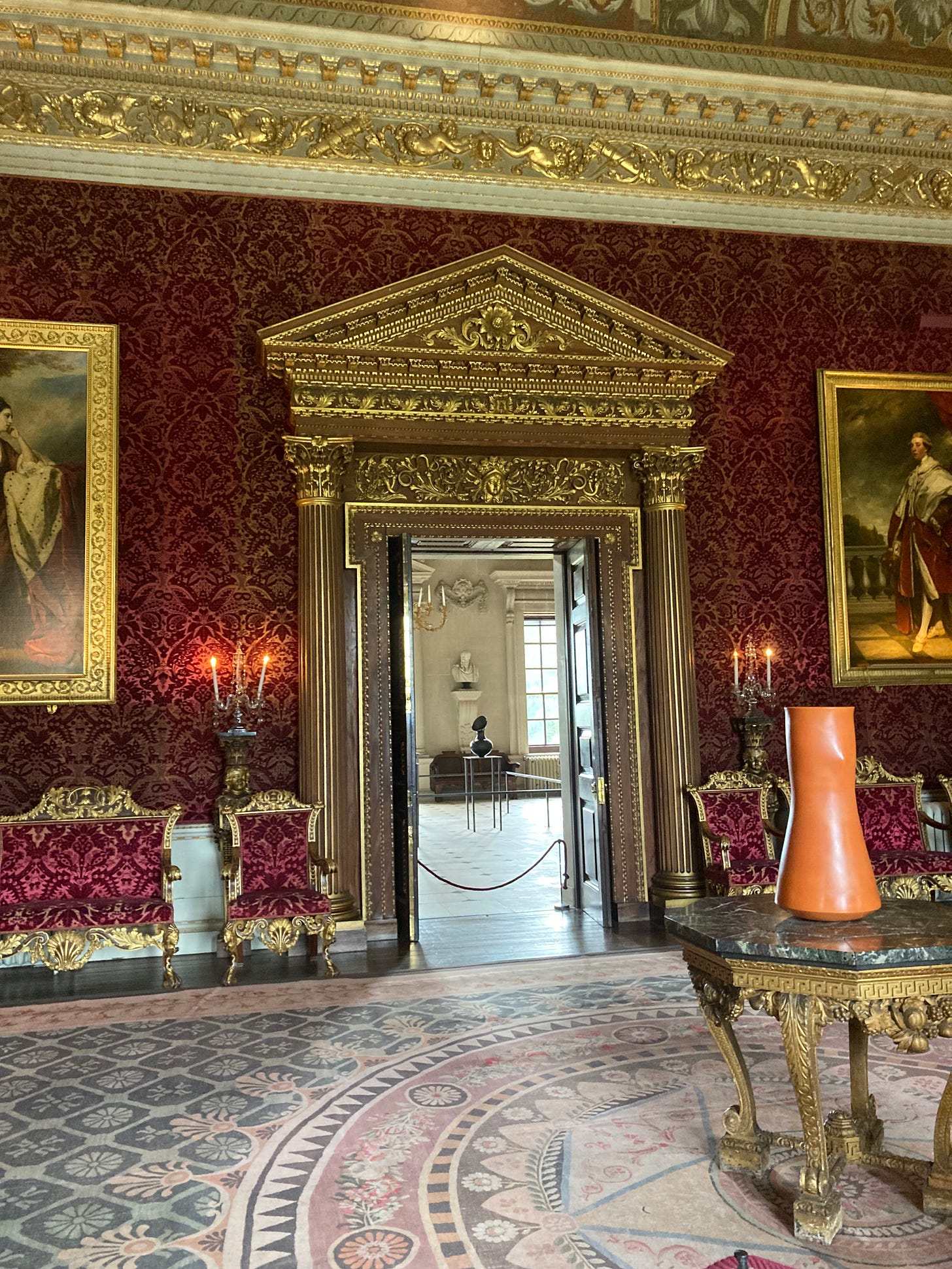

Much of what’s on offer on the inside of the house is the aristocratic standard issue: gilding, classical pediments, paintings, red damask wallpaper and a bit more gilding.

In many of the rooms, the ladies on the ceiling had found it difficult to keep their clothing on (see my previous thoughts on this here).

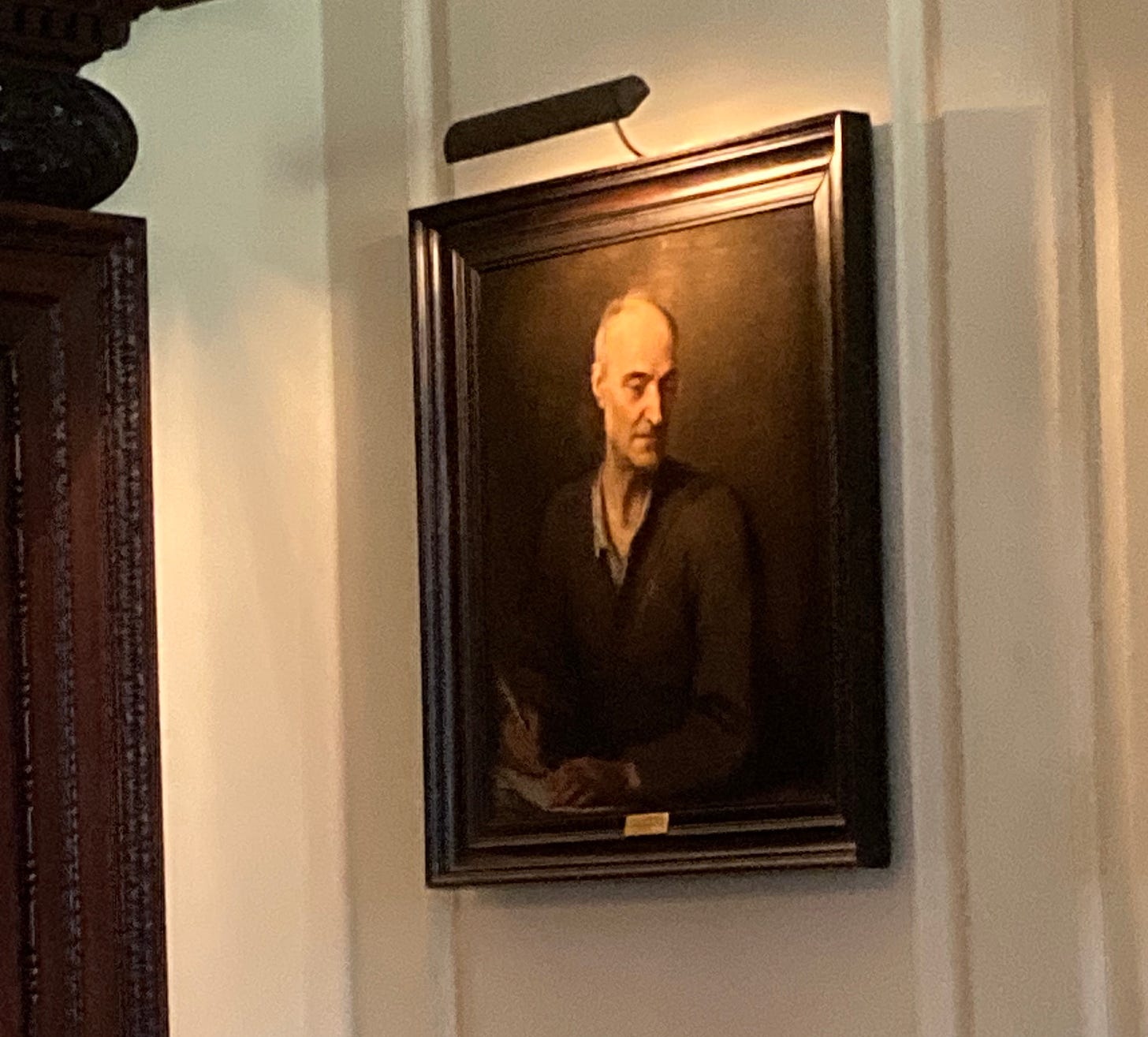

There was also, inexplicably, a picture of Dominic Cummings lurking in one corner of the Parlour.

It’s actually Juan Carreras, court philosopher, which is I am sure how Cummings likes to think of himself.

Now this painting is a rarity at Houghton as well as on the internet, mainly because it’s still in the house. Back in the late eighteenth century, the Walpoles ran out of money, partly through gambling and a dissolute lifestyle, partly from spending too much money on paintings.

As a result, hundreds of pictures were sold for a huge sum (over £50m in today’s money) to Catherine the Great in Russia, including works by Rembrandt, Rubens, Poussin and Van Dyck. In short, all the usual suspects you’d expect to find in a stately home. And now Houghton is left with a whole load of family portraits and Dominic Cummings.

On that thought, we’ll step out into the grounds to see what is on offer there. The house has been making up for all the paintings it lost in the past by buying modern art and as you approach Houghton, the posters are advertising Anthony Gormley: Time Horizon.

In a development that will come as no surprise to anyone, this installation consists of 100 casts of Gormley’s own body, dotted around the grounds in some kind of futile modern art treasure hunt. The twist which makes it art is that one initial sculpture has been installed in the basement entrance hall of the house and all the others are either on plinths or half buried to ensure that they are on the same level as this Reference Gorm.

As we come into the hall, a tour of the 99 outliers is about to set off, and I can’t help earwigging as the guide talks about how Gormley, who developed his sculptural practice in the counter-cultural 1960s, sees his work as very much a reaction against the male gaze and this is one of the reasons why he used his own body to be looked at

Now I’ve seen some of the Gorms on the way in, and feminist art was not the first thing which came to mind when I looked at them. Nor indeed was it anywhere on the list.

The Reference Gorm is buried far enough deep (although when I type this, I don’t think it is far enough deep, the heart of the earth is where we should be aiming really) to hide his genitals. This is not true of very many of the others. So my first experience of the Gorms in the landscape was not post-feminist humility, but a man waving his willy all across the landscape. (I’m not going to represent this because it’ll probably cause all sorts of problems on social media; this interview and its pictures will give you a fair idea)

But I haven’t come here to bury Anthony Gormley nor to praise him. What’s interesting to me is why these sculptures are here.

The clue is in one of the other pieces of modern art scattered around the grounds. There’s quite a bit hidden in the shrubbery, including a James Turrell light installation and this Rachel Whiteread.

In the next copse lurks another sculpture, this time by Ryan Gander.

It’s called More really shiny things that don’t mean anything and very much wants to be exactly that. “In this case, the sculpture has the scale and materiality of a work of ‘significance’ but in actual fact is simply an assortment of things that don’t really mean anything,” as one website description has it.

And so I am declaring it the patron object of art in stately homes. Because this, and the Whiteread and the Turrell and the one hundred Gorms all have a lot in common with the paintings that were sold from Houghton in the seventeenth century, and indeed with the canonical art that we see, and mostly don’t look at, every time we visit a stately home. They’re just here because they’re here. There is no point beyond that.

I mean, we all go round these places thinking that we are going to be improved by the art, but we’re not really looking at it as we amble round, and anyway, the aristocracy themselves are the proof that this process doesn’t work. They spend their entire lives living amongst Old Masters and end up as a rule interested in hounds and horses and Barbour jackets. Deborah Cavendish lived amongst a museum-quality collection at Chatsworth, but her favourite artist was Beatrix Potter

The rest of us don’t particularly benefit from paintings and sculptures being in stately homes either. And the fact that we have to pay to come and see them is one good reason why they should be elsewhere: in the street, in parks, or in public and private art galleries with public transport access and no admission fees.

So what are these artworks doing here? One answer is that it’s bait, an encouragement for us to come and pay our entrance fee and so prop up the lifestyles of the rich and entitled. I understand why artists might want to be part of this - after all, they’ve always had rich patrons - but I don’t particularly want to give money to this process myself.

The other is that they are doing the same thing that they have always done, which is sending out a message about their owners. And that message hasn’t changed since the eighteenth century. Look at me, I’m very rich and have so much money that I can buy useless objects which prove I have taste. As one recent Lord Bath put it, “I’m not all that interested in pictures myself, although I love possessing them.”

Nothing has changed since Walpole’s day. Art is simply the accoutrement of a wealthy aristocrat, a very shiny thing that does not mean anything. And if you run out of money it can always be sold, can’t it.

As ever, if you like this sort of thing, there’s going to be a whole book of it, published by Unbound. And if you really like this sort of thing, why not sign up for a copy in advance - then you get your name in the book and it gets published sooner. What’s not to like?