Unsaid

Provenance tells stories

The labels on eighteenth century furniture weren’t the only ones I took exception to in the V&A a couple of weeks ago. I was also lurking in the jewellery galleries which seem to function in part as a deposit box for the wealth of the upper classes; one, notably which they don’t have to pay for.

Here’s just one of the many loans on display - the Dufferin tiara, an emblem of class and empire and rule, worn by the wife of the Viceroy of India to Buckingham Palace, State Openings of Parliament and Coronations.

These unbelievably expensive and frivolous objects have ended up here and visible not just because they are lovely and it’s better for them to be in a museum than in a deposit box. They do glitter beautifully but whether they are being worn or sitting behind security glass in a museum, the message is much the same - look at what we own and you do not. My trinkets are worth more than your house. It’s the same story being told as when we visit a stately home. We being asked to admire the fact that the aristocracy are different to us, more wealthy and in the end somehow better. That’s why the absurd possessions of the aristocracy exist at all.

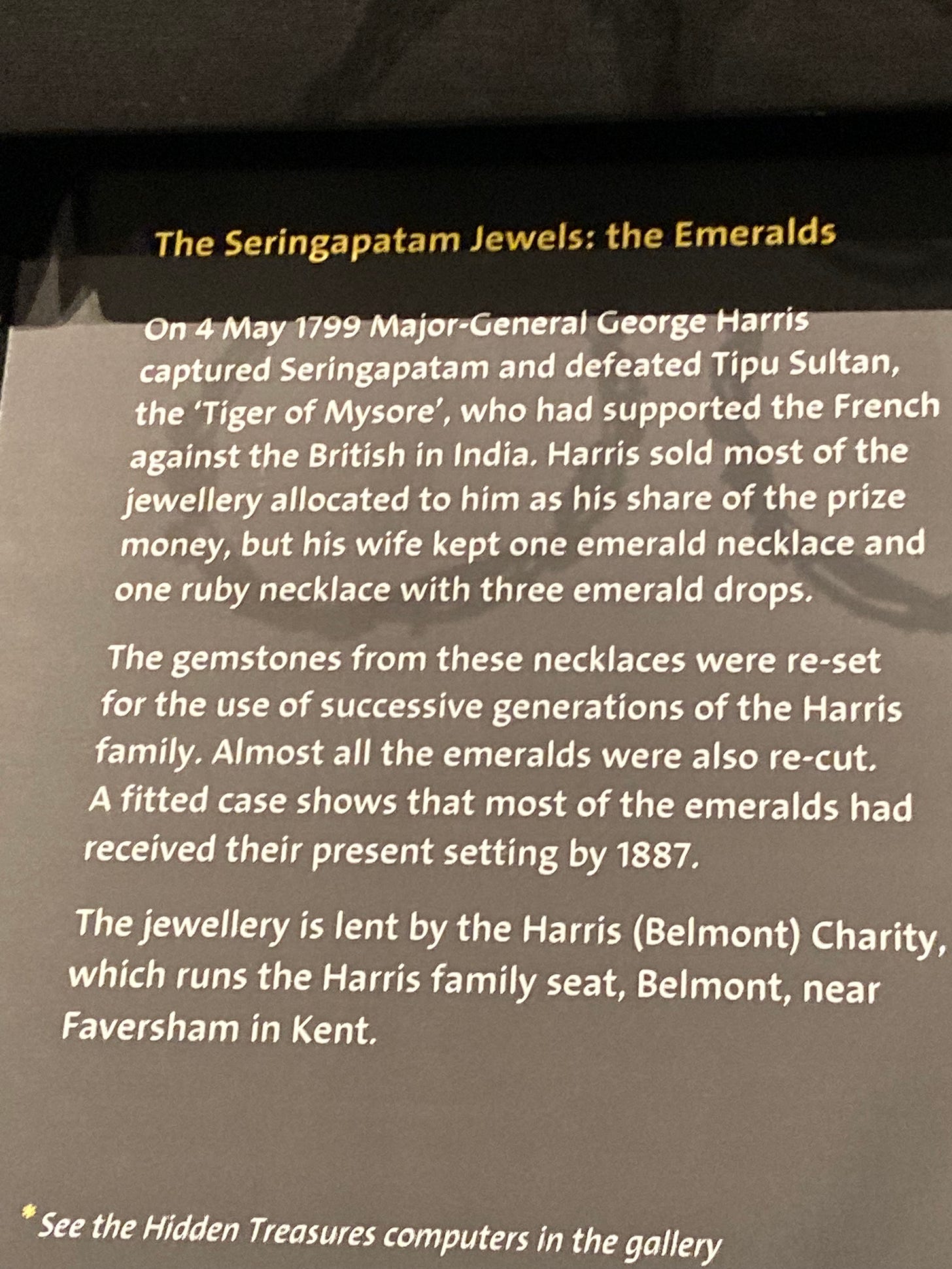

But tiaras are not the only problem sitting in plain sight. I also found these Victorian settings of rubies and emeralds - also too valuable to keep at home.

Standing with my nose pressed against the glass and without a huge amount of prior knowledge, even I could tell that the label was perhaps not telling the whole truth and that the word ‘loot’ might usefully be added in there somewhere.

If someone like me - a white middle-aged woman who’s not a historian of Empire* - thinks that a label is culturally inappropriate then the chances are something is severely wrong. So I went off to see what I could find out.

Guess what, while the jewels were, in one sense, counted out, there is rather more to the story than just that.

British soldiers were laying siege to the city of Seringapatam which was ruled by Tipu Sultan. He is known to every child of my generation because his beautiful carved wooden tiger, an automaton which eats a western solder, was on Blue Peter on average every two years throughout my childhood and back then was one of the most visited exhibits in the V&A. It’s still there.

That’s loot as well. There’s a whole story about empire and how it lingers even now in this one object too, but for today it’s a distraction. Back to the battle at Seringapatam.

Before the gems, or loot, or booty were allocated, there was a period of absolute anarchy when the British breached the walls of the city. This didn't just involve soldiers killing Tipu Sultan, desecrating his body and then raiding his extravagant treasury. Houses were burnt to the ground, the wounded left untreated amongst piles of bodies, women were found sitting half naked in amongst the ruins. Many of the gems were given to soldiers by women so scared that they “emptied their coffers and brought in whatever jewels they possessed” in the hope of buying their safety.

After a day or so, the British restored order, mostly under the orders of Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington. But this didn’t mean returning treasure to their owners. Instead they created a Prize Committee to distribute the loot and booty fairly amongst the soldiers.

One of those who got most was General Harris, who had led the campaign against the city and Tipu Sultan, and so received one eighth of the value, paid to him in gold coins and “bracelets and necklaces of pearls, rubies, emeralds and diamonds”. Harris - who became Baron Harris of Seringapatam and Mysore - sold most of what he received and became a rich man. What’s on display in the museum is just the leftovers.

Seringapatam wasn’t the worst atrocity committed by the British in India but that doesn’t make it either excusable or something to be hidden under bland phrases on a museum label. But there’s another part to the story, and that’s not being said by the V&A either.

The atrocities at Seringapatam were not committed by the British government but by a private company, run by shareholders, operated for profit. They wanted to defeat Tipu Sultan - against the wishes of the British government - for money. It’s a bit like Amazon deciding to annex Scotland in pursuit of their bottom line. And then no one mentioning it on the museum labels.

No wonder the Indians see Tipu Sultan as a freedom fighter.

I’ve not finished with this label yet either - that last paragraph will be getting a post all of its own later in the week.

*As someone who does not know enough about British Empire history, in part because of being fed stuff like Tipu Sultan’s tiger as a child, my understanding has been totally transformed by listening to the first ten episodes or so of the Empire podcast. It’s fascinating, balanced and I cannot recommend it too highly