Sometimes (that is, about once a day) I wonder what I am doing writing a book about stately homes. And at least as often someone else will ask me the same question. After all, there are plenty of reasons not to: these places are old, inert; they don’t matter any more. What’s the point?

Then something like this comes along and I reminded of all the reasons why stately homes are still very much worth challenging.

A friend alerted me to this instagram account, which is called Greathousesandestates. It has been going for 6 days and already has 10k followers. I am clearly doing something wrong.

The format is very simple, PoshBloke spends two minutes walking around the outside of a stately home, spouting banalities.

The banalities tend (there is a limit to how much of this stuff I can watch, which I have already reached) to be about continuity and tradition. There is no clue as to who he is or what his relationship is to any of the houses at all, or if he has a house of his own to which he feels this mythical obligation.

I’m starting to wonder if it’s some kind of peculiar psy-ops operation funded by Tufton Street in order to keep the Tory Party alive.

More seriously though, those ten thousand followers tell us that something important is happening here. And it’s not just this one be-tweeded idiot. Over on YouTube, hundreds of thousands of people are watching an American transmuted into posh person, Viscountess Hinchingbroke, tour round various lesser known stately homes with an attitude which covers the full gamut from delight through to full-blown flattery.

To me, this says a number of things. Firstly, stately homes do still matter, and are far from inert or defunct. Their image and existence remains an important part of our mental landscape.

The second is that they are very much associated with posh people, either with titles like the Viscountess, or just wearing the outfit, as with our flat-capped friend above.

He’s not an outlier, either. This person was welcoming us to an exhibition at Holkham at the weekend.

But what these accounts and channels are giving us is just the online equivalent of the guided tour of the house; there is no information or insight, just eye candy and the upper classes. And above all there are no questions.

This is where it gets interesting, because it’s this absence of any thinking which reveals, most of all, why stately homes matter. We have entered the realms of discourse.

Discourse - for those of you who didn't have to suffer a humanities degree in the 1980s with its accompanying load of French theorists - is basically received opinion, the unquestioned certainties of a culture. It’s the things that don’t need to be said out loud because everyone instinctively understands them, whether that’s the fact that William Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ is simultaneously very strange and at the same time a quasi-national anthem or that it’s perfectly normal for the positions of power to be dominated by Old Etonians. Discourse is just the way things are.

Part of the discourse of Englishness is that stately homes are one of the great achievements of our culture and should be preserved exactly as they are forever. No questions please. Just look at these lovely pictures of the houses.

But we should be interrogating what is going on here. Because discourse isn’t a set of beliefs which happen to be lying around on a bench, not up to much. It’s active, doing things in the world. And part of its work is transmitting power. Those who rule are generally in charge of the discourse; those underneath not so much.

And so the discourse of stately homes has a job, too. What they mean is more than just beautiful architecture and decor (if that is indeed what we are getting, see me later on this one); a well-tended garden and a lovely view with a scone for tea later. They are representing and reproducing a version of events: one in which things don’t change, everything was better in the past, a past in which the upper classes were better than the rest of us and therefore in charge.

So of course we need to ask questions about stately homes - who built them and with what money, what the architecture is telling us and who got exploited on the way. Otherwise we’ll end up trapped in the invisible web of their discourse, thinking it’s completely normal that Old Etonians rule and buy expensive wallpaper and make money at our expense and that’s just the way things are.

This is also why we need to wonder about Instagram accounts like the one I began with. Is this just a naive piece of fun from a posh public schoolboy with no self awareness? Or has it been set up by someone who understands discourse and its relation to power and who has a vested interest in keeping things just as they always have been? Answers on a postcard please.

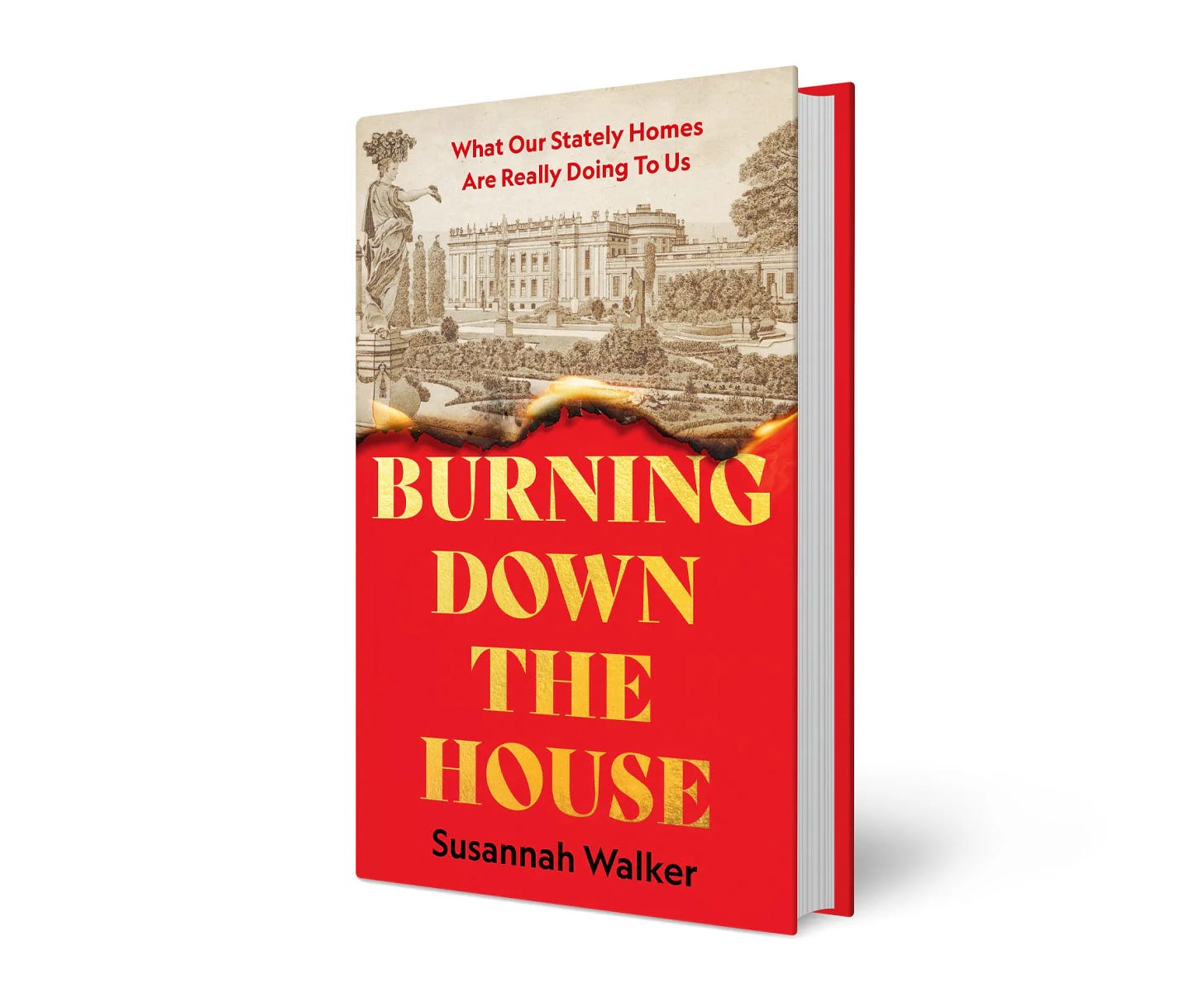

A reminder that if you like this sort of thing, a whole book of it is on the way.

It’s being published by Unbound, on a crowdfunding model, so if you pledge for a copy now not only will you get one when it is published, with your name in the back to boot, but you will help it get published sooner and then I can stop sending begging messages.

Brava, Susannah. We do need to know the history of these houses. I like that Kenwood House (near me) gives its history, whereas Floors castle in the Borders simply asks you to admire the place and the laird whose family has owned it for centuries. Open to the public for the upkeep of the place, but why does the laird (who walked past us in typical aristocratic shabby clothes) own it at all?

Wow. Talk about ‘nice but dim’; and the Holkam Hall specimen? Shallow end of the gene pool, poor beggar.