So my last post was about the gateposts of Erlestoke Park and the lesser-known stories they tell us about stately homes, in particular how, in the post war years, they were unloved and unwelcome, and how many were repurposed or were knocked down.

But if a big house disappears, then other stories vanish too: the particular histories of that place. And that’s very much the case for Erlestoke Park.

For a change, this isn’t the story of one aristocratic family and how they stayed in one place for hundreds of years. Erlestoke Park was more fluid and socially mobile. The first house was Elizabethan and was sold and sold again, until it came into the hands of Joshua Smith, the son of a merchant from Lambeth who wanted a country retreat - and possibly also the opportunity, provided by owning land and a big house, to turn into a gentleman. By 1791 he had built an impressive classical house which he lived in for almost thirty years until he died in 1819 at the age of 86.

At this point the house was sold once more - Smith had three married daughters who presumably all had homes of their own and perhaps didn’t have the money to finance a large Georgian pile. The purchaser was George Watson-Taylor. And this is where it gets important.

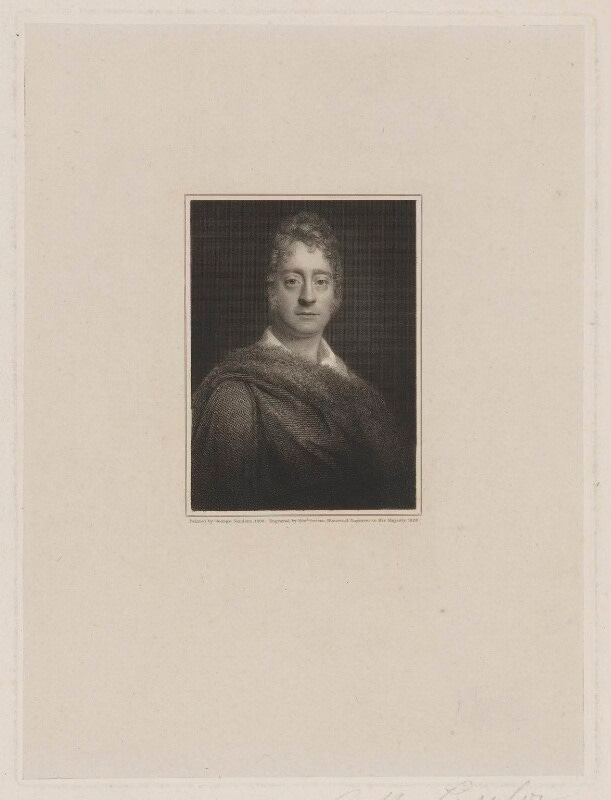

The flamboyant and wealthy Watson-Taylor (born simply Watson but who added his wife’s maiden name for reasons which will become clear in a moment) was the son of a Jamaican plantation owner, sent back to the UK to be educated. His wife, Anna, was the niece of the richest man in Jamaica, Simon Taylor. Taylor owned dozens of plantations, along with thousands of enslaved workers and was one of the very few millionaires in Regency England. His income alone was the equivalent of between six and ten million pounds a year alone.

So when Anna inherited this immense fortune in 1819, she and George and their new double-barrelled name went shopping for a house. Rumour has it that they looked at Houghton Hall, but they ended up with Erlestoke.

And that was just the start of their shopping spree. They also bought Greek vases, portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds, Hogarth paintings and a Rubens landscape.

The couple lived the high life, entertaining grandly, with even the young Princess Victoria coming to stay at Erlestoke and their outdoor entertainments being reported in the local paper.

Watson-Taylor became MP for Devizes and campaigned vociferously against the abolition of the slave trade. But, as one account has it, “when he failed in his campaign…this life-style became unsustainable”.

I’m not quite sure that’s the case. Because the Watson-Taylor family, like all other owners of enslaved people, were entitled to compensation. In their case, that was over £20,558, or almost £3.5 million pounds in today’s money. The slaves, it is worth noting, received nothing and had to continue working for their former masters for six more years, unpaid.

The real problem for the Watson-Taylors was that they spent too much. Their lavish lifestyle had already led to two vast sales of pictures, one of which happened well before slavery was abolished, and the further decline in their income simply finished them off. Although never formally declared bankrupt, George was forced into exile in Holland, and Erlestoke was let. His son did eventually return to live there thirty years later, and the house was finally sold - as so many were - just after World War 1.

All of which leaves a question about afterlives. Nowadays, with the house disappeared, the name Erlestoke just means the village and the prison. All these important stories of the wealth derived from the enslavement and exploitation of human beings do remain (much of the detail in this piece is from the excellent Legacies of British Slavery website) but they are no longer tied to a place and a house. And this in turn means that we forget how much of what we think is both ‘nice’ and ‘English’ is set on very dubious foundations.

But perhaps we also need to attach these questions to some of the other things that the family spent their money on too. The National Gallery has started to do this. Many of the paintings which George Watson-Taylor collected were of incredibly high quality, and as a result have ended up in major museums. But I am not sure that I mind too much about old master paintings. The artworks already existed, they were bought and sold with dodgy money rather than being commissioned and, while I am pleased that the National Gallery is acknowledging the connections, I don’t think it has much bearing on the work of art.

Elsewhere, though, it gets more problematic. And once again, elsewhere means the Victoria and Albert Museum, whose cataloguing really does need to take a long hard look at itself.

This is a bust of George and Anna’s son John, sculpted by John Gibson in 1816. The description tells you all about the sculptor and the provenance of the bust, but all that it says about its origins is,

This bust and those of four other Watson Taylor children formed part of the Watson Taylor Collection, Erlestoke Park, Devizes, Wilts.

All of which makes it sound quite reputable. But as you have already seen, it isn’t.

I think that the origins of this bust matter far more than the provenance of the paintings in the National Gallery, because this work was paid for by the profits from plantations, sugar and most of all enslaved people; without these it would not otherwise exist. So this slightly sickly portrait of a young boy is not an inert piece of marble to be judged on aesthetic grounds alone, however much the museum would like the to be the case.

We have to perceive the sculpture as a key part of the whole brutal economy and system, the way in which these grim practices have been laundered through art and houses and ‘culture’ and thereby made socially acceptable. It was paid for in exploitation and lives. We need to acknowledge this every time it happens, and with houses too. This is not just because it is important that we all tell the truth about how much of our heritage and past is mired in some very murky histories. More than that, if we do not challenge these objects, then past injustices do not just reverberate in the present day, they remain very much alive.

An intriguing piece which I read because I was familiar with Erlestoke Prison (from the outside) and I was delighted to learn something important. I completely agree that the provenance of great wealth from the time of the British Empire should be highlighted. I would like it all to be labelled as the proceeds of massive, globalised organised crime. Our country was bigger and better at ruthless savagery than any modern drugs cartel. And we completely got away with it.

But I think the more subtle approach will persuade more people.