We’re back here again. Wentworth Woodhouse, as promised.

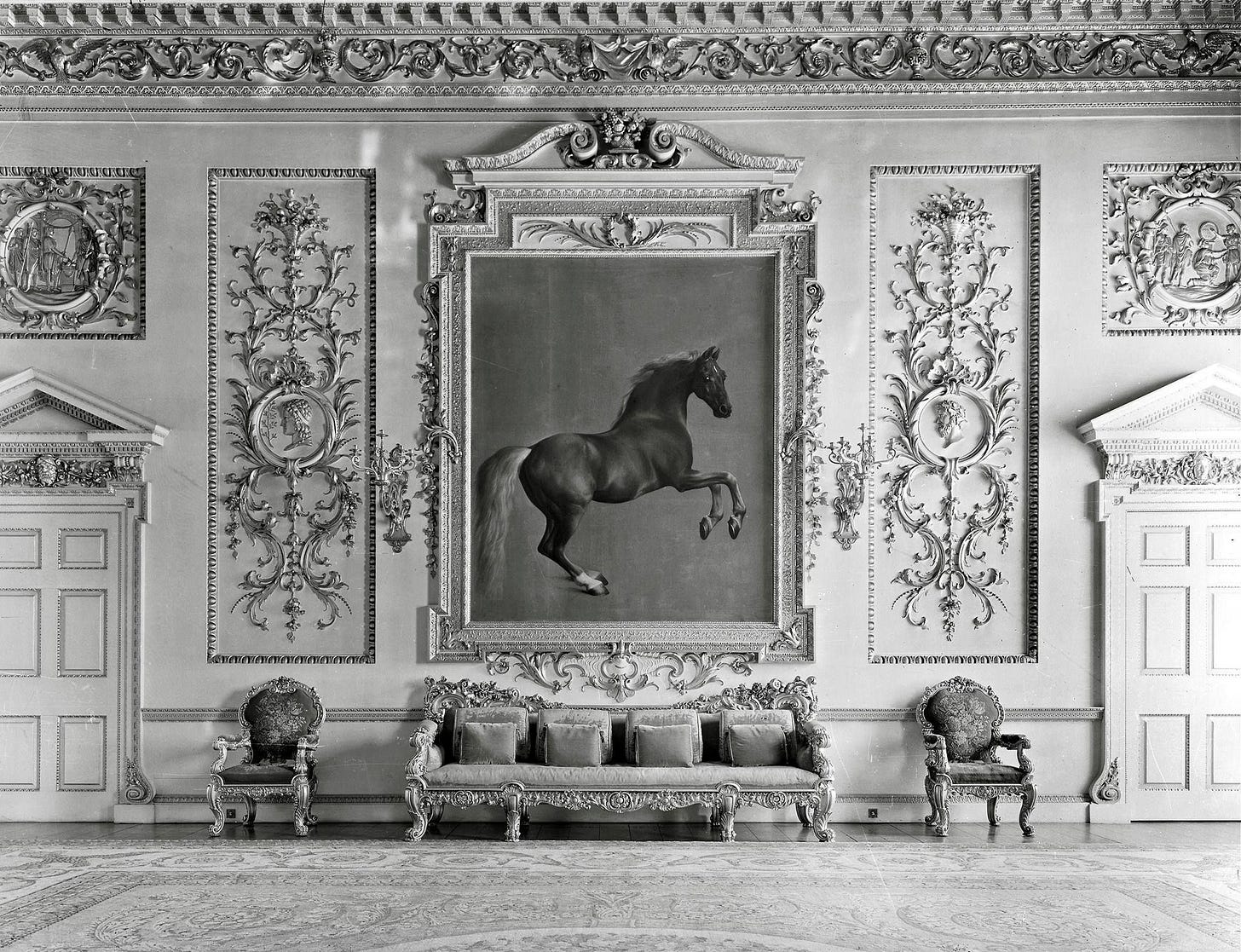

In my last post, I left a lot of questions hanging, not least why the original painting of Whistlejacket is no longer hanging on that very decorated wall.

The obvious reason is the general decline of the stately home and the aristocratic lifestyle, which has in turn led to a lot of art sales. But that’s not entirely true of Wentworth Woodhouse, which managed to hold onto its plush and servant lifestyle well into the twentieth century. Quite an achievement, because this was a ridiculously large house to keep running.

This view doesn’t even show all the house; there’s an earlier brick and stone Baroque house on the other side which is big enough to be a stately home all on its own.

There was a simple reason for why a house this immense could survive, and that was coal. While agricultural rents had gone into a tailspin, what the upper classes called ‘mineral rights’ were still very lucrative. For every ton of coal mined on their land, the Fitzwilliams earned more than the miners did, without having to run any risk of death or injury.

But in the end, coal was what did for the house. That and possibly horses.

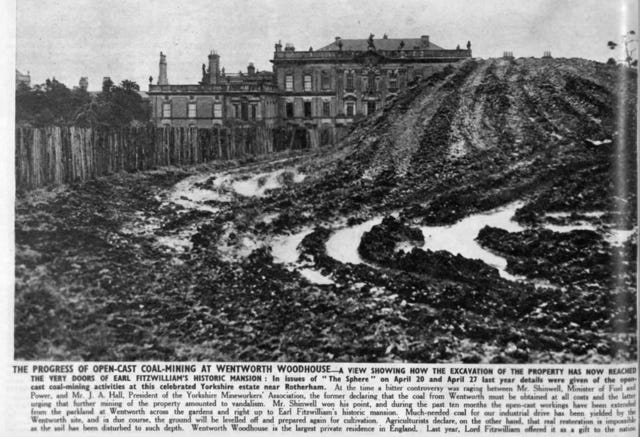

Take a look at the picture of the house again. Because something is missing. There are no gardens, nor a drive lined with ancient trees. No parkland even, just grass. This is our clue to what happened to both Wentworth Woodhouse and, in the end, Whistlejacket.

Just after the Second World War, the new Labour government, in the form of the Minister for Fuel and Power, Manny Shinwell, did two things. Firstly they ordered the nationalisation of the coal mines, which - even though they got some compensation - meant that Fitzwilliam family no longer presided over the torrents of income which had kept such a grand house going.

More specifically, Shinwell also ordered that all the ground around Wentworth Woodhouse be used for the open cast mining of coal. Many people protested and called it an act of class war and deliberate vandalism.

They could be right, because Shinwell definitely had a motive. In 1942, at what was probably the nadir of World War Two, the heir to Wentworth, Peter Fitzwilliam, bought a young horse at the Newmarket sales. And he paid the highest price ever recorded. Shinwell was unimpressed by the inequality, and said as much in a pamphlet.

Surely you are not so dull that you cannot appreciate that whatever misery you have endured, everything is as it should be in a country where at the recent yearling sales at Newmarket a filly was sold for 8,000 guineas. This sum represents about forty years wages of what is commonly regarded as a well-paid workman. Need anything more be said?

Shinwell prevailed and the diggers went in1.

The family retreated to the red brick house at the back and rented the rest to a training college for PE teachers, cannily on a full repairing lease. By 1987, the then Sheffield Polytechnic could no longer afford to maintain a rambling and decaying stately home and so moved out. At which point the Fitzwilliams decided that they could no longer afford to stay either, and put the house up for sale.

After various changes of owners and machinations over the years, the house was bought in 2017 by a public trust and is gradually being restored.

That tale of mining, class war, almost loss and eventual restoration is the story that’s always told of Wentworth Woodhouse. It’s very easy to see the house as a distillation of the fate of the country house after World War Two: a way of life which is nearly lost but then comes back as our national heritage, easily available for us all to visit. But we should not mistake it for what happened to either the Fitzwilliams or Whistlejacket.

You might imagine that the painting, along with much of the contents of the house, would have been sold in either 1947 or 1987 when the Fitzwilliams retreated. But that underestimates the scale of their remaining wealth.

To start with, Wentworth Woodhouse, despite being a two-house cut-and-shunt job and the longest facade in the country, was not the only property they owned. The family downsized to Milton Hall, the largest private house in Cambridgeshire2, and took a lot of the furniture with them. All that was the stuff which descended, under the terms of the estate, down the male line

A lot of the money and some of the outlying land, went to Peter Fitzwilliam’s only surviving daughter, Lady Juliet, who inherited enough to keep her on the Sunday Times Rich List for many years, and sufficient to allow her to become a racehorse owner and breeder, in the grand tradition of her family line.

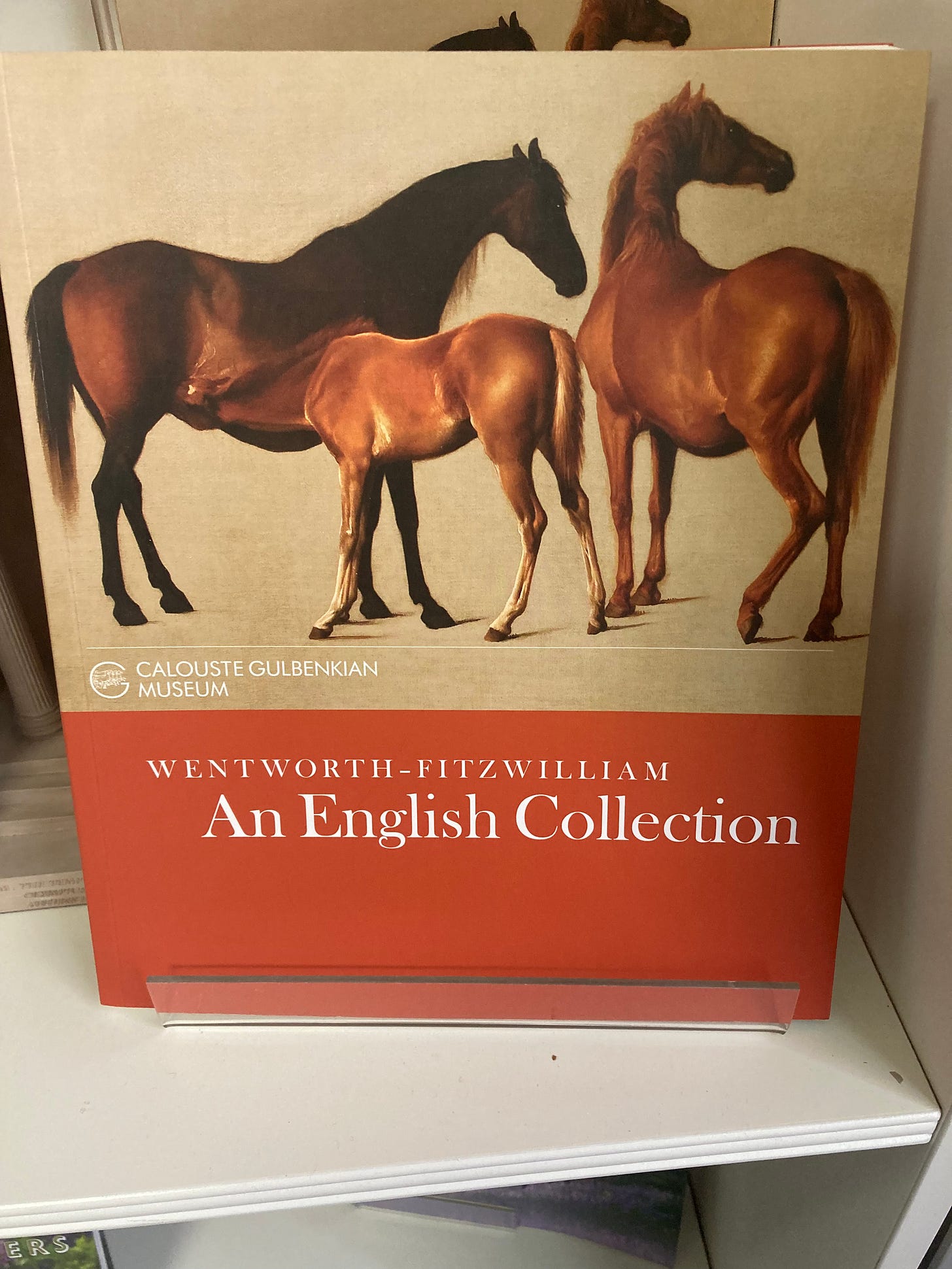

She also inherited the paintings. And kept them. So Whistlejacket - although it was often on loan - was only bought by the National Gallery in 1997. And those other two Stubbs paintings of the mares and foals? She still owns them. For all anyone knows they are on her bedroom wall, when they are not being lent to exhibitions that is.

Now on the one hand this might seem like me being picky, and possibly I am. But what I also want to show is that what happened to Wentworth Woodhouse - which has become such an icon of both change and class warfare - is not necessarily the same as what happened to its occupants.

It would be a mistake to assume that the decline of the stately home automatically means the loss of aristocratic wealth and entitlement. This may be more difficult to get rid of than even Manny Shinwell thought.

It’s possible to argue that, as the MP for a mining constituency, Shinwell also had more of a nuanced motive than that, seeing not just the racehorses but the opulence and luxury of Wentworth as an offensive contrast with the working conditions of the people he represented. More interesting detail on that here.

A house which has never been opened to the public, so who knows what’s in there.

Black Diamonds by Catherine Bailey is a fascinating account of this house and the Fitzwilliam family, and the dysfunction that money engenders.