Location, Location, Location

Passing the National Gallery yesterday, it seemed worth dipping in to have a look at their rehang. Specifically one particular painting, which is now a highlight, framed by the architecture at one end of a long run of galleries. Which probably makes it a National Treasure.

This is Whistlejacket, by George Stubbs, which is possibly - if you are the kind of person who adjudicates on these things - the greatest painting of a horse ever, done by the greatest painter of horses. It’s also very rare for the eighteenth century, because it’s just a horse on a plain background. There is something unusually modern about this, particularly when you get up close and see tiny smudges of brown paint on the green background, like faint precursors of what would become Frances Bacon.

All of which is fascinating, but it’s not why I’m writing about it. I'm interested in where the picture is, and what that does to it to how we perceive it. Because although the painting has been elevated to the status of highlight in the renewed National Gallery, this does not mean that it has always been part of our heritage. Far from it. Whistlejacket was only bought for the nation in 1997.

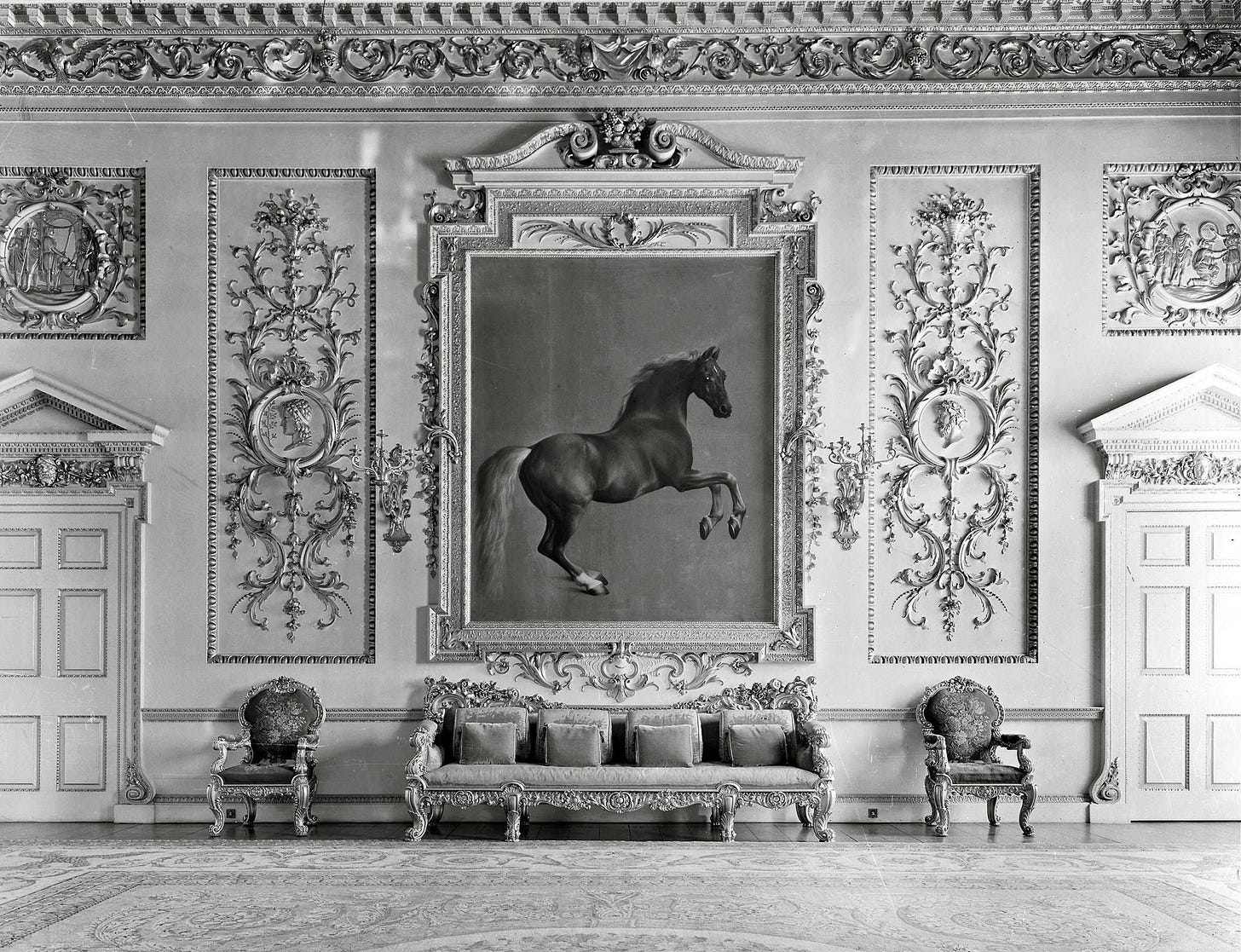

For almost two hundred years the painting hung on this wall, in South Yorkshire.

That intensely carved and gilded room is in Wentworth Woodhouse, and it was specifically designed to showcase the painting.

The room and the carvings are still there, but the furniture and the carpets are gone, and the painting is now represented by a copy.

From this, there are a whole range of stories that could be told. One is the simple tale of what happened to Wentworth Woodhouse and its collections (which I cannot believe that I haven’t written yet; perhaps next time). The other is the many ways in which horses are intertwined in the history of this house, and indeed every stately home in England.

We could also riff on the works of Walter Benjamin and consider whether it matters that the painting is now a copy, or whether this might even be an improvement; we could look at why this particular picture ended up in a national collection1. But what I’m most interested in today is how the painting itself is changed by where it has been hung. Because I think I like it far better in its simple frame in the National Gallery than as part of the gold and white walls of Wentworth Woodhouse.

Why this makes a difference is mostly down to how the painting came into existence. Stubbs was commissioned by the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham to paint Whistlejacket, one of his favourite horses. The Marquess was a courtier and twice Prime Minister, but also obsessed with horses and racing, and wealthy enough to indulge this as much as he wished. The stables that he built at Wentworth Woodhouse are immense, looking like a stately home in their own right and able to hold 84 horses, along with all their paraphernalia and staff. (Rockingham owned 200 racehorses alone, so I am not sure where he kept the others).

So when the painting hung on the walls of the Wentworth Woodhouse (in a room designed around it by a later Rockingham), it was part of not just the decorative scheme but also belonged to a whole system of signs. By depicting another of the family’s extravagant possessions, immortalised at further expense by a very well known painter, the painting carried the same meanings as the carvings and the gold and the expensive furniture. In short, they are here to explain how unimaginably rich - and therefore how powerful - the Marquess of Rockingham really was.

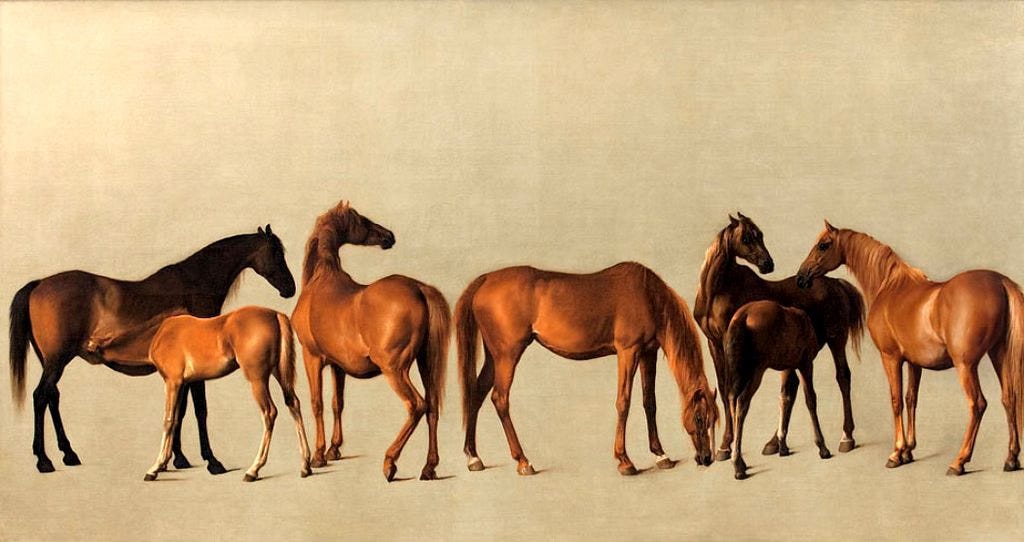

We can get into much more detail, of course. For example, this part of Wentworth Woodhouse is a relentlessly Palladian house (there’s a story here too, next time…), which means that it wants to be as much like classical Roman architecture as it can possibly manage. So it’s possible that Stubbs painted Whistlejacket without a background because it made the painting look more like a sculpted frieze. This makes much more sense when you see two other pictures that he painted for Rockingham, at about the same time, where the layered rows of horses could easily reference the carved side of a tomb or temple.

Once Stubbs’ painting is installed on the walls of the National Gallery, however, a lot of these interpretations fall away. We know, of course, in the back of our minds that the painting was commissioned by a very rich man who liked horses. But what’s paramount here is not so much the subject as the painter - even a committed seeker out of meanings like me finds themselves up close, looking at those small dark smudges of paint. The flat green background doesn’t have so much to say; among other paintings, in a place where we look at art, it becomes more one option among many.

And so I end up preferring the way things are now, with the actual Whistlejacket on the walls of the National Gallery and the copy, representing all the conspicuous consumption of horses and art and decoration, in its old frame at Wentworth Woodhouse.

So far, so straightforward. But what I also realise is that this removal of context is not necessarily better for every painting that sits, or used to sit, on the walls of a stately home. In some cases, it turns out that I am quite keen for the aristocracy to be damned by the evidence of their own art. But that too is another story all over again2.

I may have set myself a bit of a challenge here. Let’s see how many of these I can write over the next week or two.

If you want a preview of the thoughts, though, I’ve written about a couple of choice examples from Stourhead already.

I followed your link to Stourhead paintings and am still picking my jaw up from the floor. Excellent commentary!