We’re back to following the money, and this is the part that I have been meaning to write for weeks, possibly even months. The events concerned are both infuriating and frankly, not well enough known.

We’ll begin in Dyrham Park, which is owned by the National Trust, who have displayed it in a way designed to infuriate Restore Trust, by focusing on the property’s links with the trade in enslaved people. That’s not what I want to look today, however.

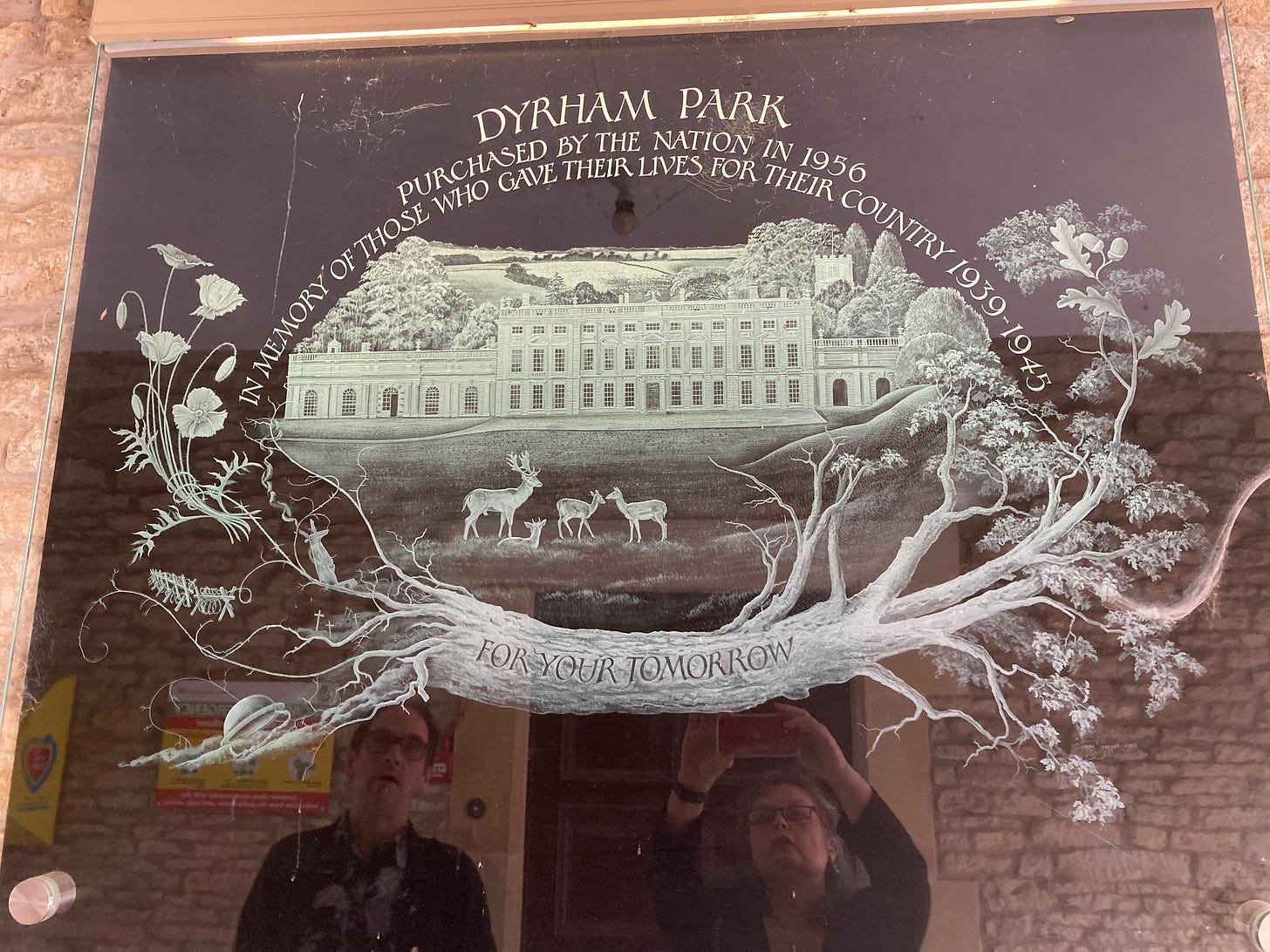

Instead, I’ve come to an obscure corner of the walkway which leads into the house, and houses this plaque (apologies for the inescapable reflection).

Now, given that Dyrham is owned and operated by the National Trust, you may be wondering why it is in memory of those who gave their lives for during the Second World War. The answer lies in three words which are missing from the plaque, which are National Land Fund.

This was set up by Hugh Dalton, who was Chancellor of the Exchequer in the shiny new post-war Labour government. And it was created to do what the title said. Money from the sale of surplus war stores was to go towards buying land for the national benefit. Dalton explained what this meant in his budget broadcast.

This money will be used to buy some of the best of our still unspoiled open country, and stretches of coast, to be preserved for ever, not for the enjoyment of a few private land-owners but as a playground and a national possession for all our people. I want the young people in particular to have free access to all the most beautiful parts of Britain.

He backed this up with cash. The fund - intended to be the nation’s memorial to the sacrifices of the war - was endowed with £50 million, the equivalent of £1.8 billion today.

For the first few years, it functioned pretty much as Dalton had intended. By 1949, it had made twenty seven different acquisitions, the vast majority of which were land and estates. Some was reserved by the government, others passed to the National Trust. A selection of properties, including a seaside house in St Merryn and a house in Cumberland, were destined to be Youth Hostels, while the Ministry of Works got two ruined cottages on Hadrian’s Wall. The only country house was Cothele, a medieval mansion which came to the Trust as part of a wider estate of 1,277 acres.

Then in 1950 comes the Gowers Report into country houses1. By this point, the vested interests of landowners had got their act together, and the report - extraordinarily for something produced under a Labour administration - decides that:

The English country house is the greatest contribution made by England to the visual arts… which is irreplaceable, and has seldom, if ever, been equalled in the history of civilisation.

I have so many arguments with this, but they are all for another day.

For now, we’re focusing on policy, and the result of the report was that from 1951 the National Land Fund could accept houses in lieu of death duties as well as land, and then in 1953 the Tories extended this again to include their contents. The shift was immense. Here are just some of the properties acquired using money from the National Land Fund.

Mount Grace Priory

Beningborough

Tatton Park

Sudbury Hall

Shugborough

Penrhyn

Baddesley Clinton

Ickworth

Melford Hall

Berrington Hall

Clevedon Court

Dyrham Park

Westwood Manor

Sissinghurst

Saltram

By 1977, as is clearly visible from their list of annual expenditure, the fund is almost entirely directed towards posh people, their houses, their art and their interests2.

a) Landed Properties

Stackpole Estate, Pembrokeshire £475,000

(b) Chattels associated with certain buildings

Clandon Park, Surrey £76,790

Attingham Park, Shropshire £29,794

(c) Objects or collections of preeminent aesthetic or historic interest:

A collection of ships' figureheads and other maritime objects £91,000

The Blenheim Archives — a collection of letters and manuscripts £342,329

The Seafield Collection of arms and armour £213,058

The Newhailes Collection of books and manuscripts £45,582

The Elton Collection of the History of Science and Technology £111,525

A 12th Century English Ivory Liturgical Comb £95,680

A sheet of studies in pen and ink and wash for "The Finding of Moses" by Paolo Veronese £11,340

The drawings by Rembrandt Van Rijn, "A Group of Musicians Listening to a Flute Player", "Tobias and Sara" and "Sacrifice of Manoah" £96,220

Portraits by Sir Anthony Van Dyck, Albert de Ligne, Prince of Brabancon and Arenberg, Rachel de Ruvigny, Countess of Southampton, Penelope Wriothesely, wife of William 2nd Lord Spencer £190,575

Several items of porcelain including Meissen figures £69,425

Total £1,848,318

In case you were wondering, this is the liturgical comb concerned, now in the V&A.

But that’s a distraction. The point is that a massive amount of money, intended for buying land which was to be free to access for anyone in the country, and creating youth hostels to help them do this, was now predominantly being used to prop up the aristocracy and their minority culture.

What’s more, in passing the houses to the National Trust, this money also often funded a situation in which the family were able to stay in part of the house3. We’re back with Michael Heseltine, why are we paying money to keep these people in places they cannot afford?

And why do we never hear about this? It was our National Memorial. And then it became theirs. Surely I am not the only person who thinks that this is an outrage.

I am not sure whether this deserves a fuller treatment another day or not. I am not sure how much of this entitlement I can take, never mind you lot.

From Hansard

The Trust are unsurprisingly very quiet about these arrangements, so while it was definitely the norm in the 1950s and even 60s, I don’t know how many remain. If anyone has any information on this, I would love to hear it.