For a change, we’re off to the British Museum. But don’t worry, the subject is still very much stately homes, but it just might take us a few minutes to arrive there.

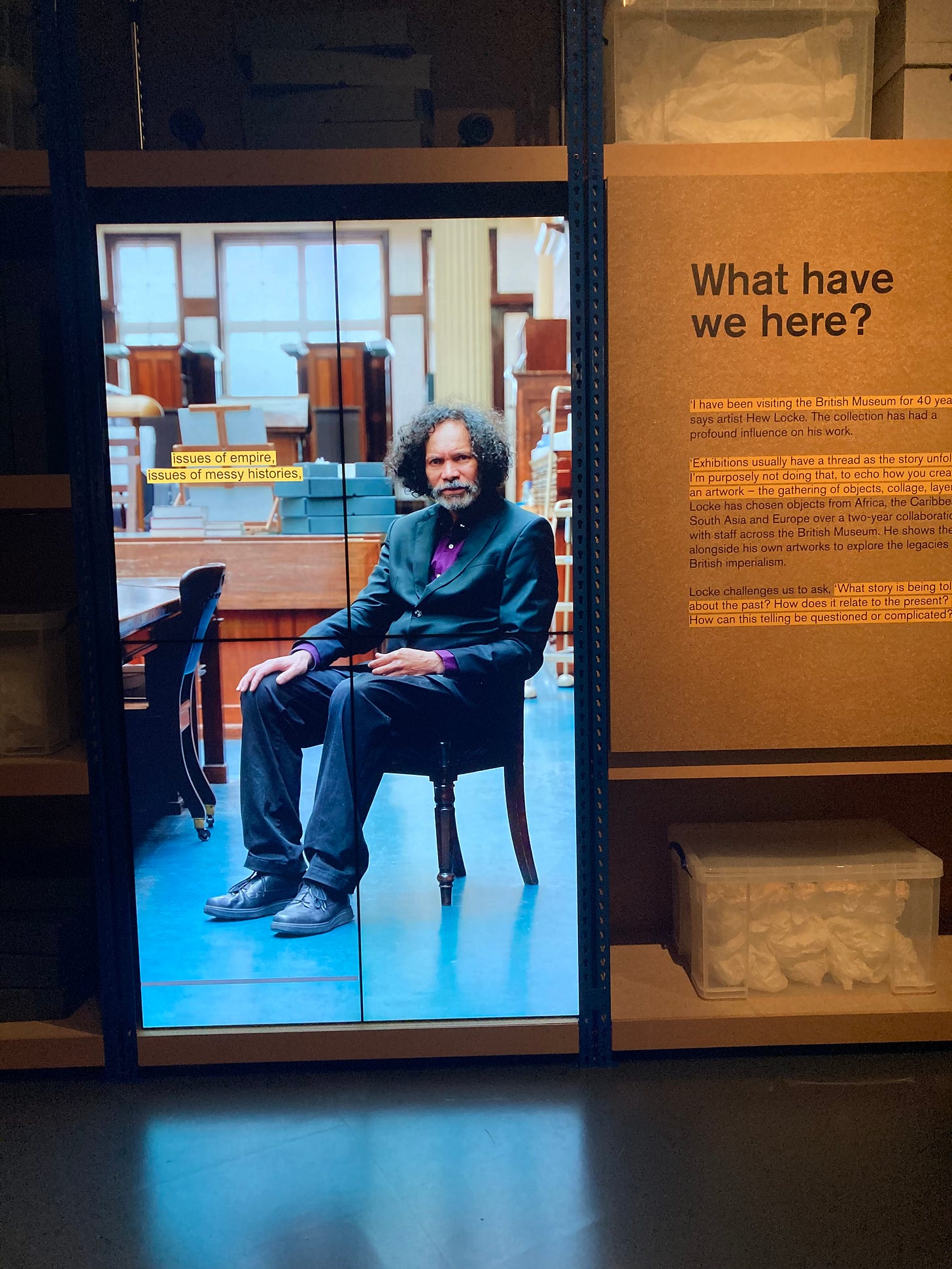

The exhibition I came to see is by artist Hew Locke, and it’s called What have we here? This is him, talking to the visitors at the start.

In one big space above the old Reading Room of the library, he’s brought together a carefully chosen set of items from the Museum’s collections intermixed with some of his own art works, and captioned them.

Along with the formal object descriptions, he’s put his own comments, printed on yellow like a post-it. In a case about the Royal African Company of England, set up by Charles II and run by his brother James, Duke of York, a print of James gets the following note:

A lot of these people [the slaves] had the initials RACE (Royal African Company of England) or DOY (Duke of York) branded on their backs, on their bodies. Once you hear that - it’s very difficult for me personally to engage with them after that.

Well, yes.

This was just the first case I looked at. The rest of the exhibition tells dozens more fascinating stories, all of which I could quite happily write down here (I photographed almost every single thing in it and then bought the catalogue too) but that’s not the point. Go and see it.

Inevitably, I found myself thinking about the displays in terms of stately homes. What would happen if we applied the same scrutiny (what have we here?) to the details of these grand houses and their contents, rather than just ambling past the statues and the furniture and the gilding on our nice days out. Locke’s exhibition gives us some interesting pointers as to how we might do this.

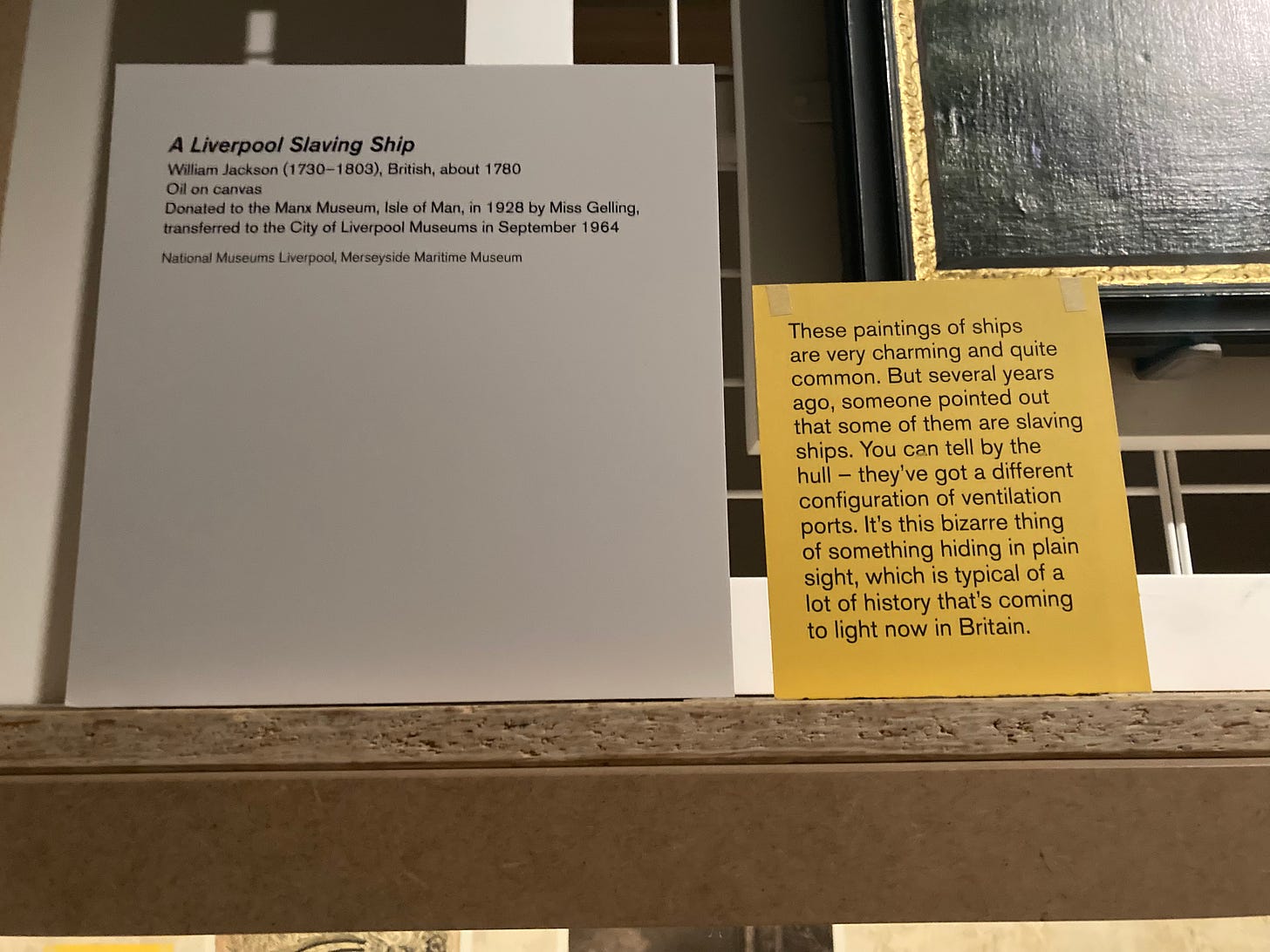

The first one is very simple. What might we notice if we examine the objects we are shown more closely? Above the case about slavery and the Duke of York is a painting of a ship. It looks like a type, the kind of obscure art that we are used to seeing - and mostly walking past - in galleries.

Until you know what you are looking at.

So much of what is in stately homes, from the mahogany doors (very much a product of the economies of enslaved labour) to the classical statues to the relentless parade of heraldry embody stories about what these houses mean and how they would like us to behave. These examples of inequality and exploitation are physically present in front of us, hiding in plain sight. So rather than just shuffling past the art and objects, all we need to do is ask questions. What have we here?

There are so many opportunities to do this in stately homes. I wrote about just one of these examples in a previous post. At Highclere (the house now also known as Downton Abbey), we queued in upstairs corridors to see the bedrooms which had belonged to fictional daughters of the house. Along the walls were hung photographs of Victorian railway opening ceremonies and also, curiously, before and after pictures of a nineteenth century bombardment.

Like so much in stately homes, none of these pictures were labelled, but I tracked them down to the opening of the Rhodesian railway (built to allow the extraction of mineral wealth from the newly colonised country) and the Anglo-Zanzibar War, which has become meme-worthy because it is the shortest war in history, lasting just thirty eight minutes.

A yellow note in that corridor from Hew Locke would have been very handy perhaps asking us what it means to display these things proudly and without comment?

Relevantly to those pictures, one of the objects that Locke displays is a model of the Maxim machine gun. This was the drone warfare of late Victorian colonialism, the new technology which made conquest inevitable.

Although Zanzibar was mostly a war of naval guns, it’s still worth noting that 500 people, most of them civilians, died from the bombardment, as set against one British sailor, who was injured. I may be going to add my own yellow post it comments to that corridor next time I find myself in Highclere.

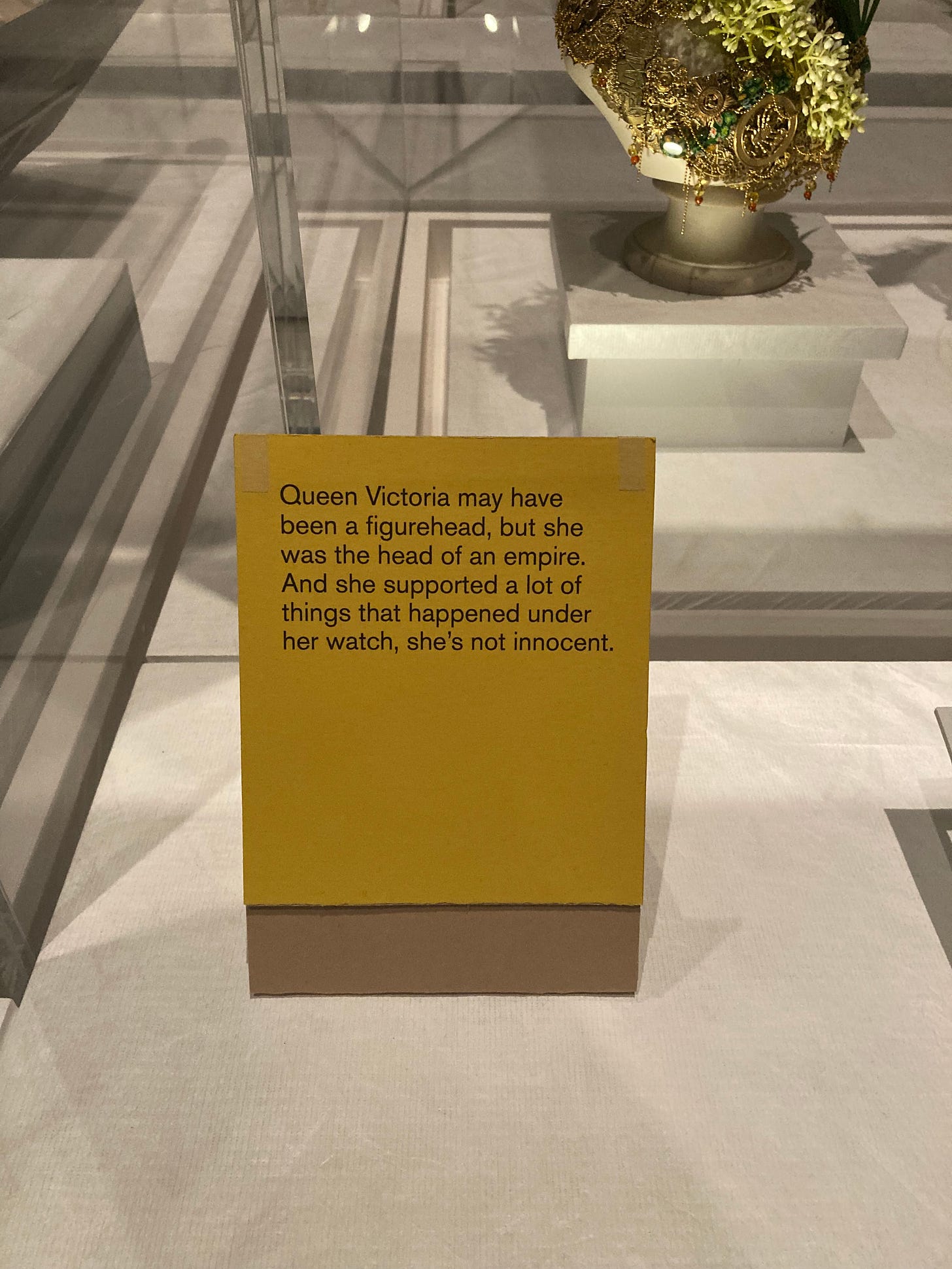

That question is potent enough on its own but in the exhibition, Locke also suggests ways in which we might look. Some of his tools are quite simple, like the exhibition caption. At the most basic level, it’s a relief to see items from Africa, Tibet and other outposts of Empire captioned as loot rather than ethnography or ‘prize money’. Other home truths are also said out loud.

See also much of the aristocracy. Their endless rows of portraits are not inert.

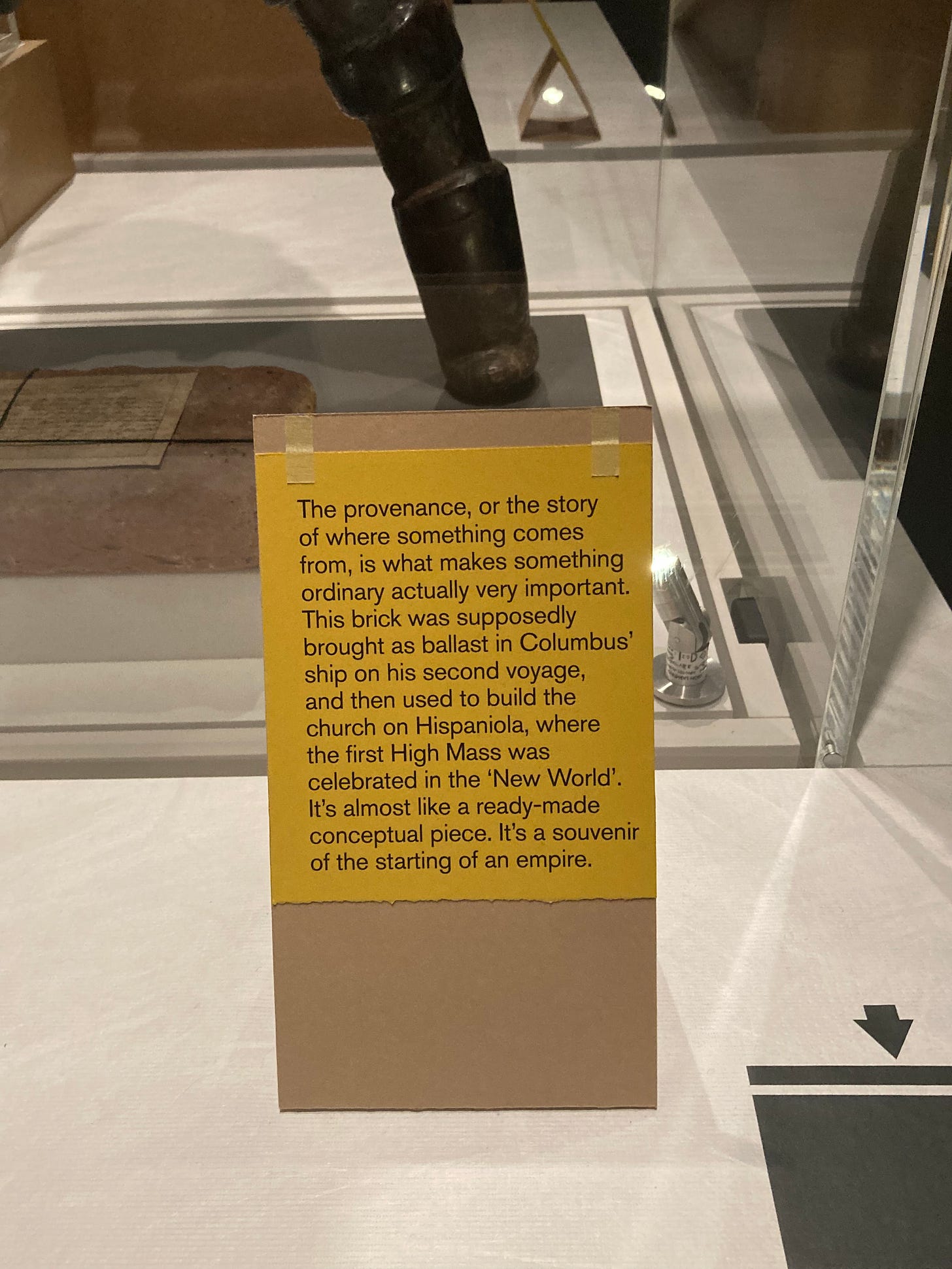

But Locke is also interested in the life stories of objects, so every single one of his labels also has a full section on provenance1.

Stately homes have no labels, less provenance. But the stories of how some of their contents arrived there would also qualify them as conceptual art pieces too.

One of the great strengths of the exhibition is that it acknowledges complexity. Locke displays his own OBE, with the word Empire in the award; there is a display on the Koh-i-noor diamond which points out that it was taken from India, but also notes that, as a gem which has been seized in war time and again, it’s quite hard to know who gets to have it back.

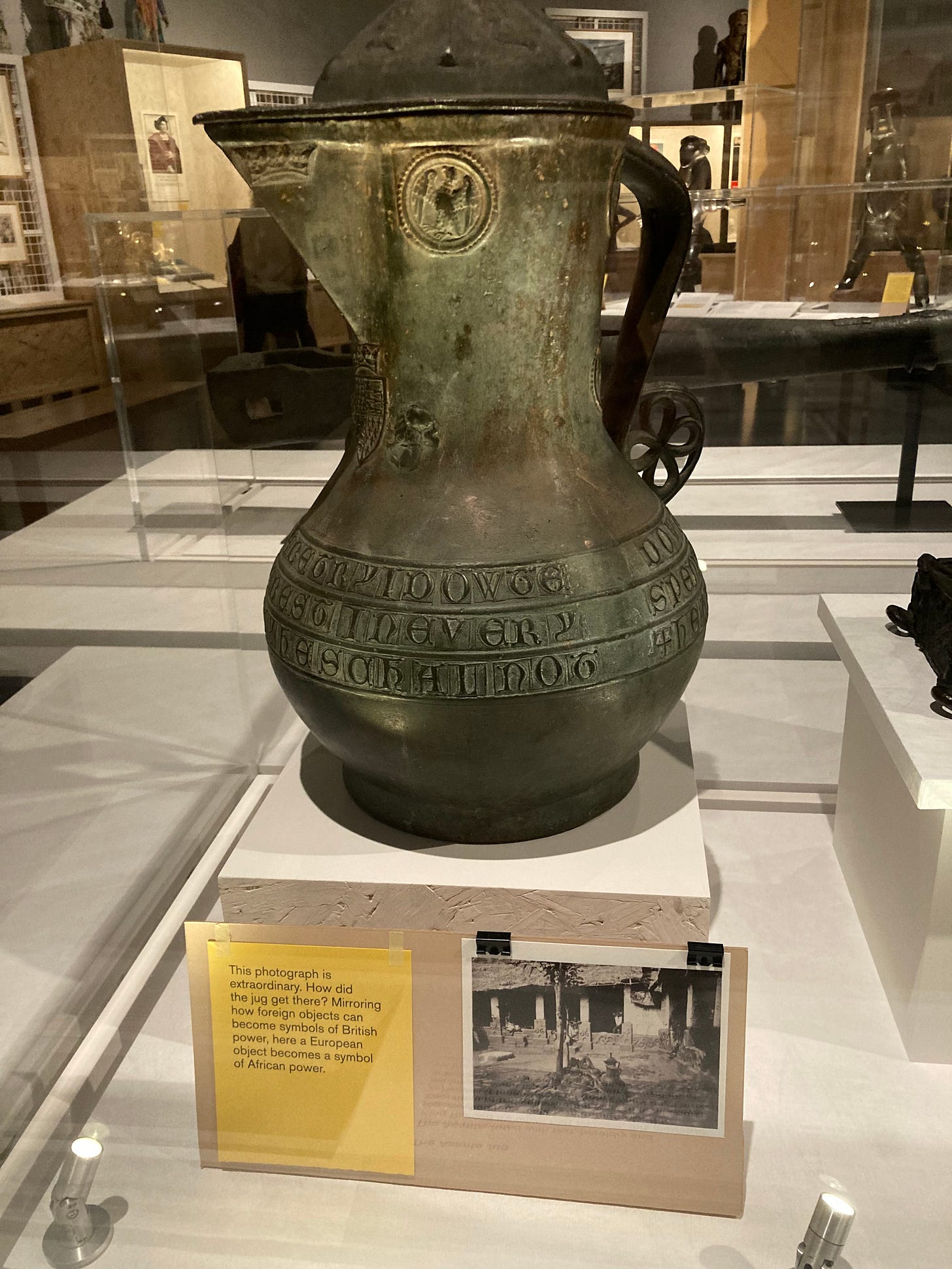

And then there is this jug.

It came to Britain after the sack of Benin City in 1897, a notorious event very much achieved by the Maxim gun. Which makes it colonial loot. Except that it really returned, because it was originally made in England in about 1390, quite possibly for Richard II. What belongs to where now?

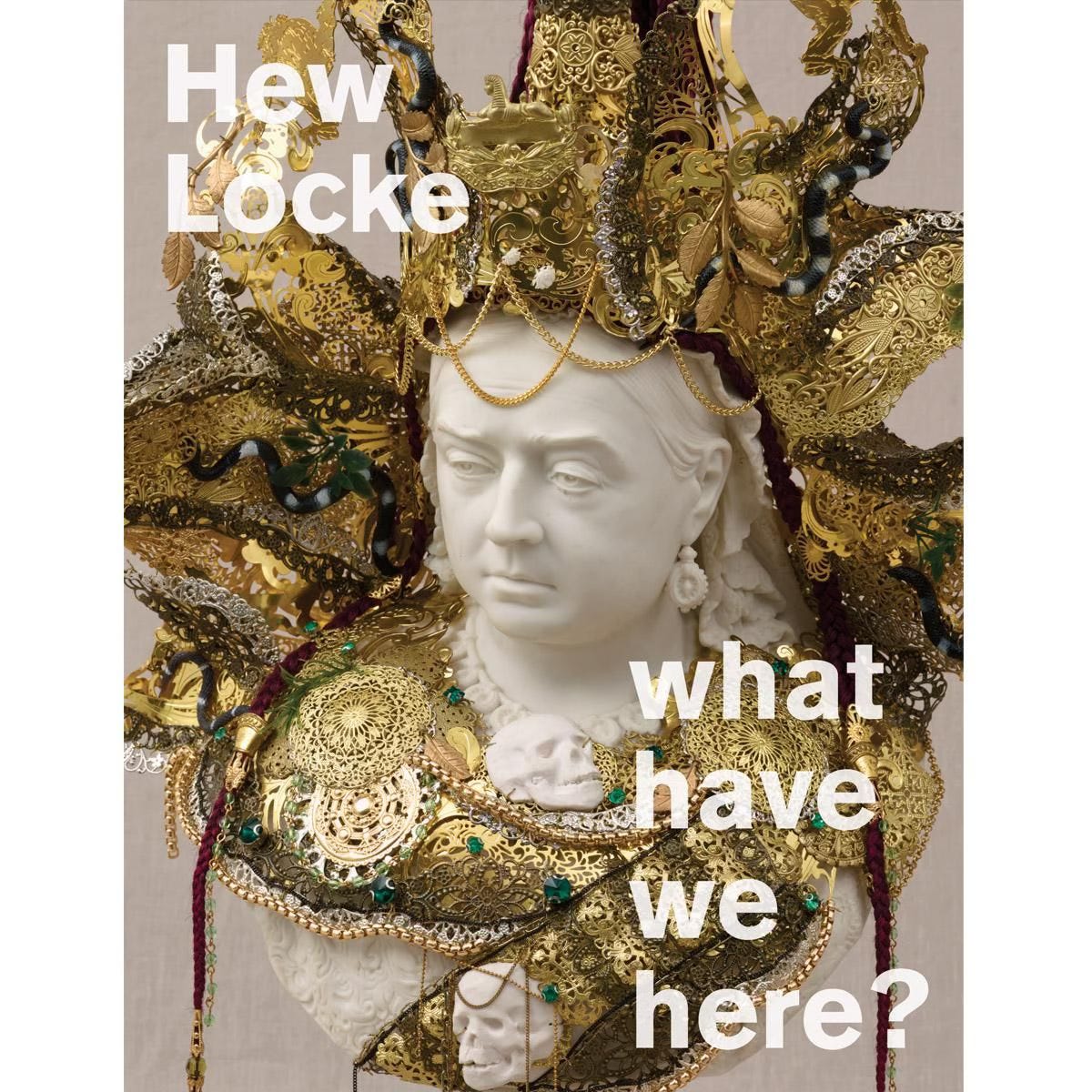

But Locke is not just reordering items from the museum; the exhibition is also full of his own art, from augmented busts of Queen Victoria to large ‘Watcher’ statues which look down from above the cases - and elsewhere in the museum - to turn the tables on the viewer. We are now under observation too. What are they making of us?

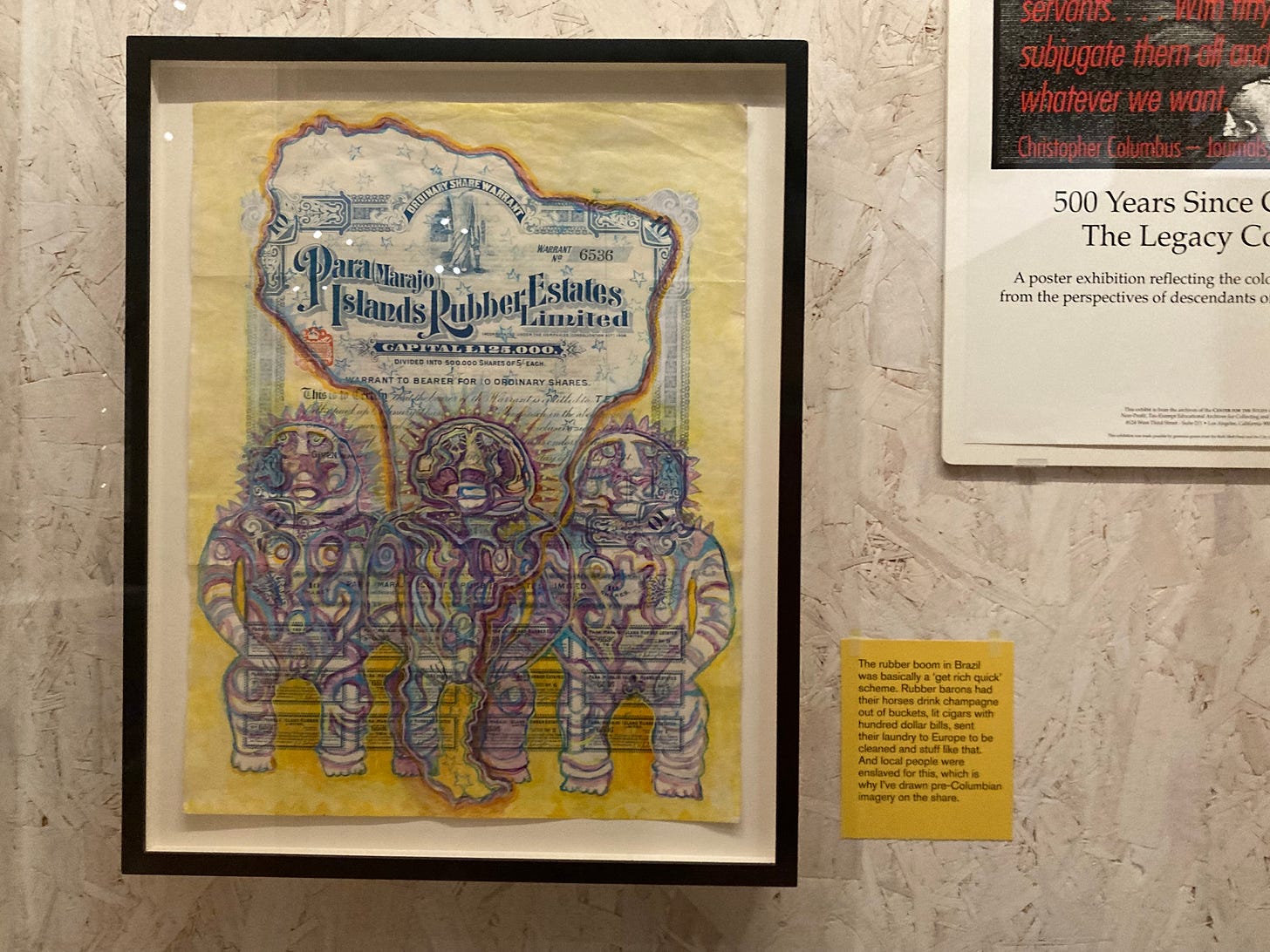

Dotted throughout the cases are also artworks on paper.

These feature Locke’s own drawings but the paper he has chosen to work on is obsolete share certificates from colonial companies. It’s a reminder of another question which we always need to be asking. Not just where did the money come from but also where did it go?

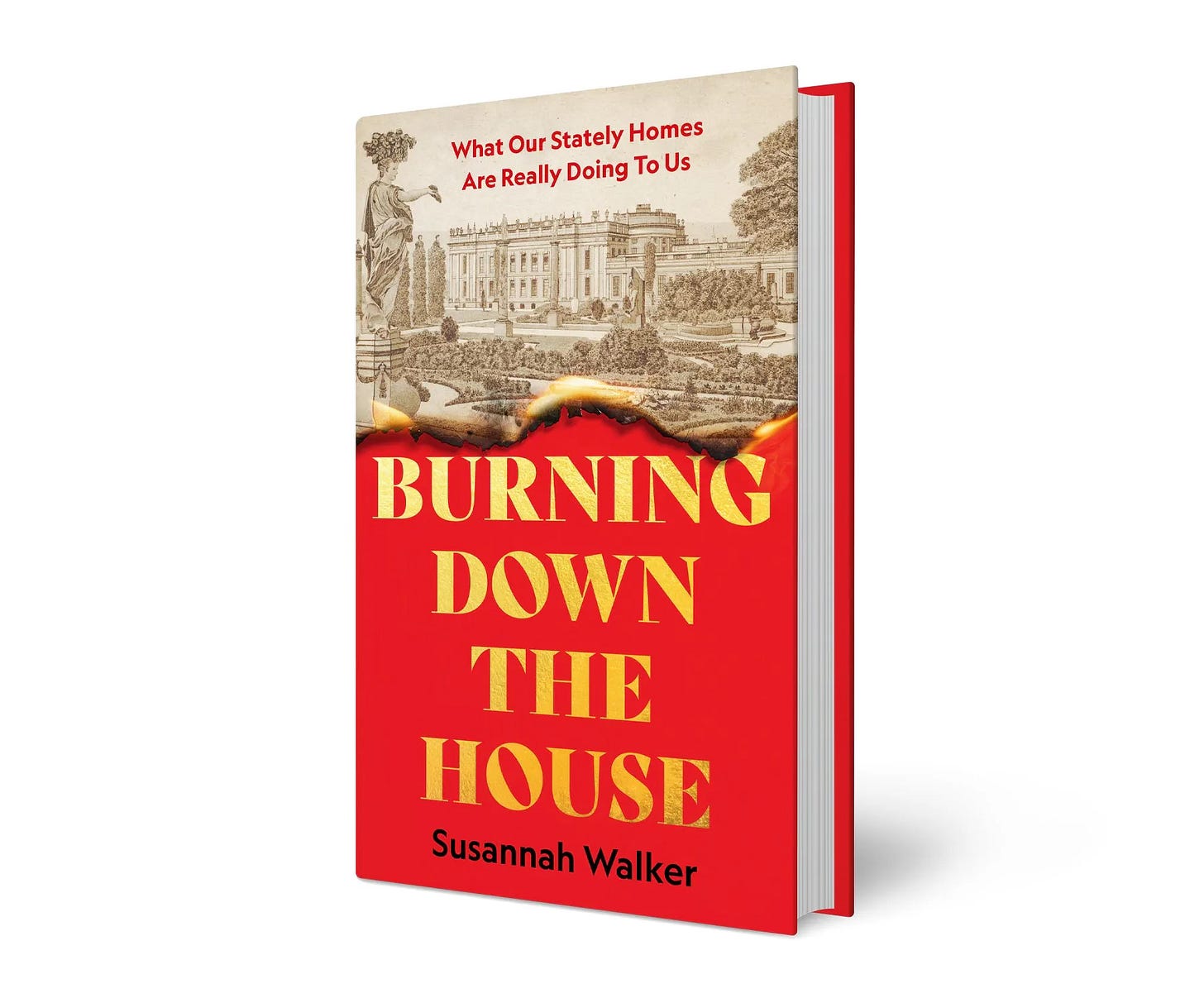

All of which in the end is to say two things. One is go and see the exhibition and draw your own conclusions (and please do tell me about it below). But the other is that Locke’s question is very much at the heart of Burning Down the House. This is the kind of engaged curiosity we need in order to examine our stately homes.

So if that appeals to you, please do pledge for an advance copy and then we can all go round the grand houses of England, a copy in hand, asking the question, what have we here?

I’ve been interested in the biographies of things for a long time (and wrote a bit about them in The Life of Stuff) but it’s a subject that museums tend to avoid. Objects are designed and made and then they appear in a glass case, but the intervening period is never mentioned. How did they live, and survive? Why was this thing chosen over another? As Locke’s provenances show, these stories are not just fascinating but also revealing. They lift the lid on the invisible mechanism which purrs beneath the bonnet of museums, revealing some of the assumptions and ideologies which power not just them but also our wider society. And, in the case of stately homes, the life stories of their contents also tell us that very little of what we see is truly authentic, left untouched for hundreds of years. In which case, we need to start asking what their purposes are?

I haven't been to the exhibition (yet) but I agree with you that it's so important to think about provenance, always digging deeper to find out where something 'really' comes from. Which unfortunately also makes me think about questioning BAME people 'where do you really come from'.